Introducing a New Genre: Cli-Fi

LINK is working now here:

@RobinRBates

Professor of literature, teacher, husband, father, liberal, Episcopalian, passionate blogger

St. Mary's City, MD

As I plan my Introduction to Literature class, which has “Nature” as its focus, I am finding useful a November Kathryn Shulz New Yorker ...

Introducing a New Genre: Cli-Fi

Friday

As I plan my Introduction to Literature class, which has “Nature” as its focus, I am finding useful a November Kathryn Shulz New Yorker article on literature and the weather. Schulz discusses how, in response to global climate change and increasingly frequent extreme weather events, a new literary genre is emerging: cli-fi.

First, however, she looks back at how over the centuries we have interpreted weather—by which she mostly means extreme weather since we don’t pay attention to the other kind. She appears to see four stages in the process:

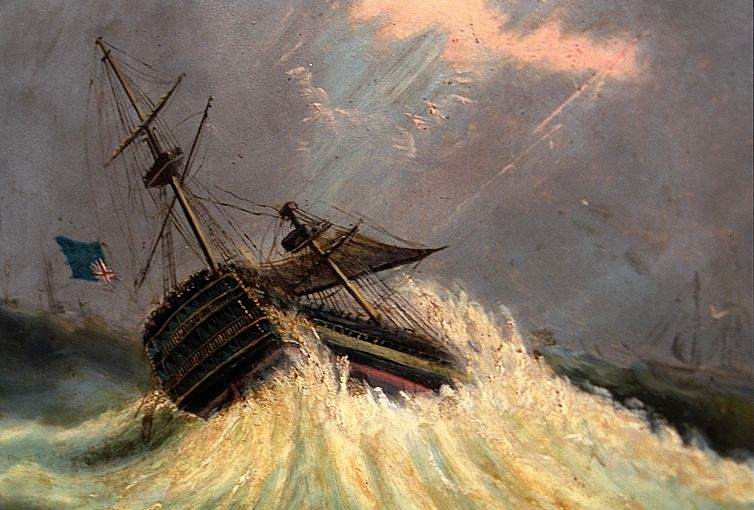

–Up until the emergence of Renaissance humanism, extreme weather was seen as the work of angry gods. Piss off Poseidon by poking out the eye of his Cyclops son or eat the cattle of the sun god Helios and you’ll be shipwrecked and all your men will be killed. God in those days punished whole nations or groups of people;

–With the Renaissance and a Protestantism that emphasized one’s personal relationship with God, extreme weather became seen as the result of individual failings. For disobeying his father, Robinson Crusoe is subjected to a series of increasingly violent storms and finally finds himself stranded on a desert island. Then, for extra measure, God sends an earthquake that nearly buries him in his cave;

–With the scientific revolution, the weather became increasingly see as uninfluenced by humans and so was regarded as merely metaphorical. Then even the metaphorical use of the weather got attacked, with John Ruskin saying that those authors who use weather to convey inner emotions (think of the storm in King Lear) are guilty of “the pathetic fallacy.” Their mistake was indicating a connection when there wasn’t one.

–Schulz says that this view prevailed for a while and extreme weather dropped out of literature (although she mentions exceptions like Grapes of Wrath). With the advent of human-caused climate change, however, weather is making a comeback.

Let’s look at each of these stages in turn. I’ve talked many times about how literature helps us make sense of the world. In ancient times humans had little control over nature, which panicked them. To feel at least somewhat secure, we feel we must have some kind of control. An explanation such as “angry gods” is one kind of explanation and it even suggests a course of action one can take: offer the deities proper obeisance.

I remember reading Homer as a child and wondering why the Greeks so often failed to offer up the proper sacrifices to Poseidon or Zeus. Didn’t they know bad things would happen? But of course, storytellers are Monday morning quarterbacks: looking back at a disaster, they conclude that someone did something wrong. They don’t mention those times when nothing bad happened even though sacrifices were omitted.

Nature became more personal when our relationship with the gods, set in motion by Jesus but coming into fruition with Renaissance humanism and the Protestant reformation, became one-on-one. Shulz gives an excellent example in the change in Milton’s Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve eat of the fruit. Before they took the bite, I tell my students, the weather was like Southern California all the time. After, not so much.

We get a sense of what is in store when Eve reaches for the fruit:

So saying, her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the Fruit, she pluck’d, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her Works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost…

And then when Adam does:

…he scrupl’d not to eatAgainst his better knowledge, not deceav’d,But fondly overcome with Femal charm.Earth trembl’d from her entrails, as againIn pangs, and Nature gave a second groan,Skie lowr’d, and muttering Thunder, som sad dropsWept at compleating of the mortal SinOriginal…

At this point God steps in and gets His angels to tilt the earth and rearrange the weather. (Among his other talents, Milton knows his science.)Here’s a sampling from what is a long passage:

While the Creator calling forth by name

His mightie Angels gave them several charge,As sorted best with present things. The SunHad first his precept so to move, so shine,As might affect the Earth with cold and heatScarce tolerable, and from the North to callDecrepit Winter, from the South to bringSolstitial summers heat….

To the Winds they set

Thir corners, when with bluster to confound

Sea, Aire, and Shoar, the Thunder when to rowle

With terror through the dark Aereal Hall.

Some say he bid his Angels turne ascanse

The Poles of Earth twice ten degrees and more

From the Suns Axle; they with labour push’d

Oblique the Centric Globe…

Romantic poetry, of course, saw nature as a reflection of the soul, but, as the 19th century progressed, weather came to be seen as lacking special significance. It was just part of the impersonal universe that one had to deal with. Some authors are very good at emphasizing ironic contrast, with nature oblivious to human tragedy. In Mary Oliver’s “Lost Children,” for instance, a father frantically searching for his lost daughter is serenaded by the “thrush’s gorgeous and amoral voice.”

With our present-day actions resulting in super storms and killer droughts, however, humans are once again discovering that they have special relationship with nature. As a result, weather is once more becoming significant in literature. As Schulz observes,

What used to be idle chitchat about the unusually warm day or last weekend’s storm has become both premonitory and polarizing. Nor is there any innate melodrama left in meteorology. Weather is, instead, at the heart of the great drama of our time.

And further:

It is not just that the facts about climate change have become clear; it is that, in establishing those facts, the scientific model of weather, which eclipsed the symbolic one in the nineteenth century, is now colliding with it. These days, the atmosphere really does reflect human activity, and, as in our most ancient stories, our own behavior really is bringing disastrous weather down on our heads. Meteorological activity, so long yoked to morality, finally has genuine ethical stakes.

And because literature never fails to take up the great dramas of our time, new kinds of books are being written:

That shift began to be reflected in literature in the later decades of the twentieth century, with the emergence of the genre now known as cli-fi—short for climate fiction, and formed by analogy to “sci-fi.” As that suggests, novels about the weather have tended to congregate in genre fiction. The dystopian novelist J. G. Ballard wrote about climate change before the climate was known to be changing; later, Kim Stanley Robinson, Margaret Atwood, and many others used the conventions of science fiction to create worlds in which the climate is in crisis. More recently, though, books about weather are displaying a distinct migratory pattern—farther from genre fiction and closer to realism; backward in time from the future and ever closer to the present. See, among others, Ian McEwan’s “Solar,” Barbara Kingsolver’s “Flight Behavior,” Nathaniel Rich’s “Odds Against Tomorrow,” Karen Walker’s “The Age of Miracles,” Jesmyn Ward’s “Salvage the Bones,” and Dave Eggers’s “Zeitoun.”

I particularly appreciate Schulz’s concluding observation that stories about apocalyptic weather disasters are, in one sense, escapist: they give one the illusion of control without one having to do anything. That’s how the stories of an angry Poseidon also work. Back then, however, there really was little one could do.

We, on the other hand, can take dramatic steps to reduce the threat of climate change. The challenge, as Schulz points out, is not to fatalistically accept what is happening but rather to figure out what to do next:

But apocalyptic stories are ultimately escapist fantasies, even if no one escapes. End-times narratives offer the terrible resolution of ultimate destruction. Partial destruction, displacement, hunger, want, weakness, loss, need—these are more difficult stories. That is all the more reason we should be glad writers are beginning to tell them: to help us imagine not dying this way but living this way. To weather something is, after all, to survive.

As I plan my Introduction to Literature class, which has “Nature” as its focus, I am finding useful a November Kathryn Shulz New Yorker article on literature and the weather. Schulz discusses how, in response to global climate change and increasingly frequent extreme weather events, a new literary genre is emerging: cli-fi.

First, however, she looks back at how over the centuries we have interpreted weather—by which she mostly means extreme weather since we don’t pay attention to the other kind. She appears to see four stages in the process:

–Up until the emergence of Renaissance humanism, extreme weather was seen as the work of angry gods. Piss off Poseidon by poking out the eye of his Cyclops son or eat the cattle of the sun god Helios and you’ll be shipwrecked and all your men will be killed. God in those days punished whole nations or groups of people;

–With the Renaissance and a Protestantism that emphasized one’s personal relationship with God, extreme weather became seen as the result of individual failings. For disobeying his father, Robinson Crusoe is subjected to a series of increasingly violent storms and finally finds himself stranded on a desert island. Then, for extra measure, God sends an earthquake that nearly buries him in his cave;

–With the scientific revolution, the weather became increasingly see as uninfluenced by humans and so was regarded as merely metaphorical. Then even the metaphorical use of the weather got attacked, with John Ruskin saying that those authors who use weather to convey inner emotions (think of the storm in King Lear) are guilty of “the pathetic fallacy.” Their mistake was indicating a connection when there wasn’t one.

–Schulz says that this view prevailed for a while and extreme weather dropped out of literature (although she mentions exceptions like Grapes of Wrath). With the advent of human-caused climate change, however, weather is making a comeback.

Let’s look at each of these stages in turn. I’ve talked many times about how literature helps us make sense of the world. In ancient times humans had little control over nature, which panicked them. To feel at least somewhat secure, we feel we must have some kind of control. An explanation such as “angry gods” is one kind of explanation and it even suggests a course of action one can take: offer the deities proper obeisance.

I remember reading Homer as a child and wondering why the Greeks so often failed to offer up the proper sacrifices to Poseidon or Zeus. Didn’t they know bad things would happen? But of course, storytellers are Monday morning quarterbacks: looking back at a disaster, they conclude that someone did something wrong. They don’t mention those times when nothing bad happened even though sacrifices were omitted.

Nature became more personal when our relationship with the gods, set in motion by Jesus but coming into fruition with Renaissance humanism and the Protestant reformation, became one-on-one. Shulz gives an excellent example in the change in Milton’s Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve eat of the fruit. Before they took the bite, I tell my students, the weather was like Southern California all the time. After, not so much.

We get a sense of what is in store when Eve reaches for the fruit:

So saying, her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the Fruit, she pluck’d, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her Works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost…

And then when Adam does:

…he scrupl’d not to eatAgainst his better knowledge, not deceav’d,But fondly overcome with Femal charm.Earth trembl’d from her entrails, as againIn pangs, and Nature gave a second groan,Skie lowr’d, and muttering Thunder, som sad dropsWept at compleating of the mortal SinOriginal…

At this point God steps in and gets His angels to tilt the earth and rearrange the weather. (Among his other talents, Milton knows his science.)Here’s a sampling from what is a long passage:

While the Creator calling forth by name

His mightie Angels gave them several charge,As sorted best with present things. The SunHad first his precept so to move, so shine,As might affect the Earth with cold and heatScarce tolerable, and from the North to callDecrepit Winter, from the South to bringSolstitial summers heat….

To the Winds they set

Thir corners, when with bluster to confound

Sea, Aire, and Shoar, the Thunder when to rowle

With terror through the dark Aereal Hall.

Some say he bid his Angels turne ascanse

The Poles of Earth twice ten degrees and more

From the Suns Axle; they with labour push’d

Oblique the Centric Globe…

Romantic poetry, of course, saw nature as a reflection of the soul, but, as the 19th century progressed, weather came to be seen as lacking special significance. It was just part of the impersonal universe that one had to deal with. Some authors are very good at emphasizing ironic contrast, with nature oblivious to human tragedy. In Mary Oliver’s “Lost Children,” for instance, a father frantically searching for his lost daughter is serenaded by the “thrush’s gorgeous and amoral voice.”

With our present-day actions resulting in super storms and killer droughts, however, humans are once again discovering that they have special relationship with nature. As a result, weather is once more becoming significant in literature. As Schulz observes,

What used to be idle chitchat about the unusually warm day or last weekend’s storm has become both premonitory and polarizing. Nor is there any innate melodrama left in meteorology. Weather is, instead, at the heart of the great drama of our time.

And further:

It is not just that the facts about climate change have become clear; it is that, in establishing those facts, the scientific model of weather, which eclipsed the symbolic one in the nineteenth century, is now colliding with it. These days, the atmosphere really does reflect human activity, and, as in our most ancient stories, our own behavior really is bringing disastrous weather down on our heads. Meteorological activity, so long yoked to morality, finally has genuine ethical stakes.

And because literature never fails to take up the great dramas of our time, new kinds of books are being written:

That shift began to be reflected in literature in the later decades of the twentieth century, with the emergence of the genre now known as cli-fi—short for climate fiction, and formed by analogy to “sci-fi.” As that suggests, novels about the weather have tended to congregate in genre fiction. The dystopian novelist J. G. Ballard wrote about climate change before the climate was known to be changing; later, Kim Stanley Robinson, Margaret Atwood, and many others used the conventions of science fiction to create worlds in which the climate is in crisis. More recently, though, books about weather are displaying a distinct migratory pattern—farther from genre fiction and closer to realism; backward in time from the future and ever closer to the present. See, among others, Ian McEwan’s “Solar,” Barbara Kingsolver’s “Flight Behavior,” Nathaniel Rich’s “Odds Against Tomorrow,” Karen Walker’s “The Age of Miracles,” Jesmyn Ward’s “Salvage the Bones,” and Dave Eggers’s “Zeitoun.”

I particularly appreciate Schulz’s concluding observation that stories about apocalyptic weather disasters are, in one sense, escapist: they give one the illusion of control without one having to do anything. That’s how the stories of an angry Poseidon also work. Back then, however, there really was little one could do.

We, on the other hand, can take dramatic steps to reduce the threat of climate change. The challenge, as Schulz points out, is not to fatalistically accept what is happening but rather to figure out what to do next:

But apocalyptic stories are ultimately escapist fantasies, even if no one escapes. End-times narratives offer the terrible resolution of ultimate destruction. Partial destruction, displacement, hunger, want, weakness, loss, need—these are more difficult stories. That is all the more reason we should be glad writers are beginning to tell them: to help us imagine not dying this way but living this way. To weather something is, after all, to survive.

1 天前 - Friday.

As I plan my Introduction to Literature class, which has “Nature” as its focus, I am finding useful a November Kathryn Shulz New Yorker ...

您已造訪這個網頁 2 次。上次造訪日期:2016/1/9

No comments:

Post a Comment