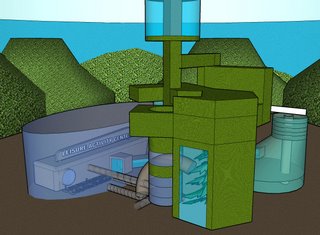

''Polar City'' illustration by Taiwanese artist Deng Cheng-hong

Q.& A. w/a ''Cli-Fi'' Activist, w/Professor Robin Bates at ''Better Living Through Beowulf'' blog

http://disq.us/93la12

A Talk with a Cli-Fi Activist

Tuesday

I’ve been having e-mail conversations with Dan Bloom, a former journalist who informally coined the term cli-fi (for climate fiction) in 2008 in a blog post to Hollywood producers without really thinking much about it at first. Dan has now become tireless in promoting novels that will promote awareness of climate change.

I like the cli-fi label because, at first glance, it appears to be a sub-genre of sci-fi. The overlap isn’t complete, however—includes Margaret Atwood but not Barbara Kingsolver—meaning that it also appears to have science fiction’s potential to generate its own sub-genres. It could well evolve as science fiction has evolved.

While sci-fi became identified as a genre in the 1920s and came into its own in in the 1950s, its origins can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries (the Laputans in Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein). This was a time when science and technology were first perceived to have a significant influence over our lives. Now sci-fi generates a rich array of works, from high literature to pulp fiction, not to mention numerous hybrids (sci-fi westerns, sci-fi noir, sci-fi horror, etc.).

Since human-caused climate change will increasingly influence our lives in the 21st century, I fully expect to see climate fiction follow a similar trajectory.

So far, cli-fi seems to be showing up mainly as futurist dystopian and disaster fiction. I’ve noted how even a contemporaneously set novel like Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (2012), while realistic, is filled with apocalyptic imagery (Ezekiel’s cherubim, Noah’s flood, Moses’s burning bush).

New genres don’t develop in a vacuum. Authors attracted to the genre seek each other out, magazines are formed, and (in this day and age) websites and blogs go into action. Dan Bloom’s website The Cli-Fi Report both takes note of and seeks to promote new climate fiction Here are excerpts from an e-mail interview I had with Dan:

Bates: When did you realize that anthropogenic global warming (AGW) was a problem?

Bloom: I was following the news about a warming world as far back as the 1970s and I even wrote a disaster novel in 1975, set in a flooded 2025 Manhattan. I sent the manuscript to New York literary agent, and one of his interns returned it with a note saying, “Interesting theme but your characters never come alive. Thanks for sending, though.” I never tried my hand at writing a novel again, but it was a good learning curve, and it taught me about the New York book industry.

Climate change caught my attention again when I was working at a Tokyo newspaper in the 1990s and we sent one of our reporters to Rio for the first big climate talks. His reports back to the paper made a big impression on me then. But I didn’t become personally involved until 2006.

I was in Taiwan when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a major report saying basically that if we don’t clean up our act soon, then our goose is cooked. I knew I had to do something.

I got in touch with James Lovelock, who had written an article in The Financial Times about the Earth as a living organism. He encouraged me to raise the alarm and I have been blogging ever since. The following year, I was encouraged when the New York Times wrote a piece about my essay on “polar cities.”

Bates: And how did you arrive at the name for the genre?

Bloom: In one of my blogs in 2008, when trying to find a Hollywood producer for a movie idea, I typed out the words “cli-fi movie” and the term was born. In 2011 I commissioned Jim Laughter (pronounced Lauder) to write a cli-fi novel, titled Polar City Red. We marketed the book as a “cli-fi thriller” and published it on Earth Day 2012. Margaret Atwood retweeted one of my tweets, informing her 600,000 followers that “there’s a new genre called cli-fi.” With Atwood’s book, the cli-fi term gained traction.

It received a second boost later that year when climate scientist Judith Curry at Georgia Tech, in her blog Climate Etc., discussed 25 cli-fi novels, past and present, including Polar City Red. The following year, in a story headlined “A New Genre Is Born: Cli-Fi,” NPR did a five minute segment on two new books about climate issues: Nathiel Rich’s Odds against Tomorrow and Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior. At that point the term went viral.

Bates: What impact do you believe cli-fi can have?

Bloom: I have always loved literature that has an impact, books like On the Beach, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Jungle, The Stranger, Animal Farm, and Flight Behavior. For me, the best of cli-fi does two things: it delivers a powerful and emotional story and it pushes the reader to wake up to the existential threat that man-made global warming poses to future generations. So good cli-fi is both a great read and a call to action, either direct or indirect.

If it doesn’t wake us up, it’s just escapist entertainment. I am not interested anymore in escapism. We are facing a dire threat to our continued existence within the next 30 generations. I especially hope for cli-fi that will reach high school and college students.

Bates: How does cli-fi achieve these aims more effectively than non-fictional treatment of climate issues?

Non-fiction is good but charts and stats and photos only go so far. A great novel, on the other hands, hits the reader in the gut and leaves them with the feeling, “I must do something about this issue.”

Bates: There’s suspicion in certain literary quarters towards “social cause fiction” — which is to say, fiction that puts the cause that a work is propounding above aesthetic concerns. Is that something you worry about?

Bloom: The novel must be a novel, written with power. Otherwise it is just a comic book. But given how much of a threat climate change poses to humankind, one can’t quibble with a novel that wakes people up, whether it is great or pulp fiction. I think we need all kinds of novels. A pulp fiction cli-fi novel that does what On the Beach did for nuclear awareness would work wonders. It’s up to writers to write and literary critics can determine the line between classic and pulp later.

Furthermore, there’s a place for so-so cli-fi out there, self-published by hobby weekend writers. Most of them could never be published by a major publishing house. But that’s okay because they are exploring the issues. My own failed attempts at writing a novel, after all, brought me to where I am today.

Sometimes the most effective cli-fi literature, like Flight Behavior, doesn’t appear to be promoting a cause. You can tell that it raised awareness, however, because it was attacked by rightwing climate deniers.

Flight Behavior, I’d say, is one of the best cli-fi novels so far, a 10. Solar, a satiric yarn by Ian McEwan, I’d award a 5.

Bates: Tell us about your work alerting the world to climate change.

Bloom: It’s really just a hobby that fell in my lap with that now famous NPR broadcast just a few days after my 65th birthday. I am not a professional public relations person and I’m not an academic with a PhD or a literary critic or a theorist. Nor do I get paid. I have been working on behalf of cli-fi since 2006, 24/7 without any days off or vacations.

I do it as a labor of love and I haven’t looked back since. It’s solo work, there’s no staff, no office, no funding, no secretary or support crew, no university sponsorship or backing, and I don’t even own a computer! I work out of a smoky internet cafe in Taiwan, renting the computers there by the hour.

It is the most meaningful work I have done in my life.

I’ve been having e-mail conversations with Dan Bloom, a former journalist who informally coined the term cli-fi (for climate fiction) in 2008 in a blog post to Hollywood producers without really thinking much about it at first. Dan has now become tireless in promoting novels that will promote awareness of climate change.

I like the cli-fi label because, at first glance, it appears to be a sub-genre of sci-fi. The overlap isn’t complete, however—includes Margaret Atwood but not Barbara Kingsolver—meaning that it also appears to have science fiction’s potential to generate its own sub-genres. It could well evolve as science fiction has evolved.

While sci-fi became identified as a genre in the 1920s and came into its own in in the 1950s, its origins can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries (the Laputans in Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein). This was a time when science and technology were first perceived to have a significant influence over our lives. Now sci-fi generates a rich array of works, from high literature to pulp fiction, not to mention numerous hybrids (sci-fi westerns, sci-fi noir, sci-fi horror, etc.).

Since human-caused climate change will increasingly influence our lives in the 21st century, I fully expect to see climate fiction follow a similar trajectory.

So far, cli-fi seems to be showing up mainly as futurist dystopian and disaster fiction. I’ve noted how even a contemporaneously set novel like Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (2012), while realistic, is filled with apocalyptic imagery (Ezekiel’s cherubim, Noah’s flood, Moses’s burning bush).

New genres don’t develop in a vacuum. Authors attracted to the genre seek each other out, magazines are formed, and (in this day and age) websites and blogs go into action. Dan Bloom’s website The Cli-Fi Report both takes note of and seeks to promote new climate fiction Here are excerpts from an e-mail interview I had with Dan:

Bates: When did you realize that anthropogenic global warming (AGW) was a problem?

Bloom: I was following the news about a warming world as far back as the 1970s and I even wrote a disaster novel in 1975, set in a flooded 2025 Manhattan. I sent the manuscript to New York literary agent, and one of his interns returned it with a note saying, “Interesting theme but your characters never come alive. Thanks for sending, though.” I never tried my hand at writing a novel again, but it was a good learning curve, and it taught me about the New York book industry.

Climate change caught my attention again when I was working at a Tokyo newspaper in the 1990s and we sent one of our reporters to Rio for the first big climate talks. His reports back to the paper made a big impression on me then. But I didn’t become personally involved until 2006.

I was in Taiwan when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a major report saying basically that if we don’t clean up our act soon, then our goose is cooked. I knew I had to do something.

I got in touch with James Lovelock, who had written an article in The Financial Times about the Earth as a living organism. He encouraged me to raise the alarm and I have been blogging ever since. The following year, I was encouraged when the New York Times wrote a piece about my essay on “polar cities.”

Bates: And how did you arrive at the name for the genre?

Bloom: In one of my blogs in 2008, when trying to find a Hollywood producer for a movie idea, I typed out the words “cli-fi movie” and the term was born. In 2011 I commissioned Jim Laughter (pronounced Lauder) to write a cli-fi novel, titled Polar City Red. We marketed the book as a “cli-fi thriller” and published it on Earth Day 2012. Margaret Atwood retweeted one of my tweets, informing her 600,000 followers that “there’s a new genre called cli-fi.” With Atwood’s book, the cli-fi term gained traction.

It received a second boost later that year when climate scientist Judith Curry at Georgia Tech, in her blog Climate Etc., discussed 25 cli-fi novels, past and present, including Polar City Red. The following year, in a story headlined “A New Genre Is Born: Cli-Fi,” NPR did a five minute segment on two new books about climate issues: Nathiel Rich’s Odds against Tomorrow and Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior. At that point the term went viral.

Bates: What impact do you believe cli-fi can have?

Bloom: I have always loved literature that has an impact, books like On the Beach, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Jungle, The Stranger, Animal Farm, and Flight Behavior. For me, the best of cli-fi does two things: it delivers a powerful and emotional story and it pushes the reader to wake up to the existential threat that man-made global warming poses to future generations. So good cli-fi is both a great read and a call to action, either direct or indirect.

If it doesn’t wake us up, it’s just escapist entertainment. I am not interested anymore in escapism. We are facing a dire threat to our continued existence within the next 30 generations. I especially hope for cli-fi that will reach high school and college students.

Bates: How does cli-fi achieve these aims more effectively than non-fictional treatment of climate issues?

Non-fiction is good but charts and stats and photos only go so far. A great novel, on the other hands, hits the reader in the gut and leaves them with the feeling, “I must do something about this issue.”

Bates: There’s suspicion in certain literary quarters towards “social cause fiction” — which is to say, fiction that puts the cause that a work is propounding above aesthetic concerns. Is that something you worry about?

Bloom: The novel must be a novel, written with power. Otherwise it is just a comic book. But given how much of a threat climate change poses to humankind, one can’t quibble with a novel that wakes people up, whether it is great or pulp fiction. I think we need all kinds of novels. A pulp fiction cli-fi novel that does what On the Beach did for nuclear awareness would work wonders. It’s up to writers to write and literary critics can determine the line between classic and pulp later.

Furthermore, there’s a place for so-so cli-fi out there, self-published by hobby weekend writers. Most of them could never be published by a major publishing house. But that’s okay because they are exploring the issues. My own failed attempts at writing a novel, after all, brought me to where I am today.

Sometimes the most effective cli-fi literature, like Flight Behavior, doesn’t appear to be promoting a cause. You can tell that it raised awareness, however, because it was attacked by rightwing climate deniers.

Flight Behavior, I’d say, is one of the best cli-fi novels so far, a 10. Solar, a satiric yarn by Ian McEwan, I’d award a 5.

Bates: Tell us about your work alerting the world to climate change.

Bloom: It’s really just a hobby that fell in my lap with that now famous NPR broadcast just a few days after my 65th birthday. I am not a professional public relations person and I’m not an academic with a PhD or a literary critic or a theorist. Nor do I get paid. I have been working on behalf of cli-fi since 2006, 24/7 without any days off or vacations.

I do it as a labor of love and I haven’t looked back since. It’s solo work, there’s no staff, no office, no funding, no secretary or support crew, no university sponsorship or backing, and I don’t even own a computer! I work out of a smoky internet cafe in Taiwan, renting the computers there by the hour.

It is the most meaningful work I have done in my life.

pre-interview

http://betterlivingthroughbeowulf.com/introducing-a-new-genre-cli-fi/

I recently sat down with Professor Robin Bates in Maryland, who teaches English at St. Mary's College there, to chat via email about the rise of the cli-i genre over the past few years, and its backstory, its pre-history, and most importantly of all, its future.

Although Dr Bates introduced me on his blog as ''someone who is tireless in promoting cl-fi novels that hopefully will promote awareness of climate change,'' there is in fact a huge team worldwide of cli-fi academics, media commentators, book reviewers, literary critics and novelists who themselves have been busy as well promoting the cli-fi meme/motif/genre/buzzword over the past few years as well, from Scott Thill to Rodge Glass, from Maddie Stone to Stephanie Lemenager, from Emma Drabble to Margaret Atwood, each in their own way, dozens of people, hundreds, a veritable army of people using their own personal writing and commentary platforms to help make the world more aware of the emergtence of this important new genre: cli-fi.

Dr Bates said he likes the cli-fi label because while at first to some it appears to be a sub-genre of post-modern literature, it also has the potential to generate its own identity as a separate and indepdendent genre, which is in fact the direction it has always been going in.

While cli-fi was never a part of sci-fi and never even a subgenre of sci-fi, it surely has been enjoying an evolution similar to that of the science fiction of yore and an intersting future awaits this rising new genre. While not replacing SF, cli-fi nevertheless stands on its own now as a stand-alone genre of its own making, and is giving sci-fi a run for its money.

Professor Bates noted that while sci-fi became identified as a genre in the 1920s and came into its own in in the 1950s, it origins can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries (the Laputans in Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein). That was a time when science and technology were perceived to have an increasingly powerful influence on human life. And now, in 2016, of course, sci-fi generates a rich array of works, from high literature to pulp fiction, not to mention its many hybrids (sci-fi westerns, sci-fi noir, sci-fi horror, etc.), as Dr Bates put it so well.

''Since human-caused climate change [AGW] will increasingly influence our lives in the 21st century, I fully expect to see cli-fi follow a similar trajectory," Bates says, noting:

"So far, cli-fi seems to be showing up mainly as futurist dystopian and disaster fiction. I’ve noted how even a contemporaneously set novel like Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (2012), while realistic, is filled with apocalyptic imagery (Ezekiel’s cherubim, Noah’s flood, Moses’s burning bush). '

As Bates framed the discusssion, ''new genres don’t develop in a vacuum." Authors attracted to a particular genre seek each other out, magazines and ezines are formed, anthologies are published, and (in this day and age) websites and blogs go into action.

And yes, this website -- a sub-site of The Cli-Fi Report http://cli-fi.net/ --

both takes note of and seeks to promote new genre of cli-fi for a readership of academics, media criticis, novelists and literary theorists worldwide.

Here are some excerpts from the e-mail interview Dr Bates conducted. [Out-takes from the published interview will appear elsewhere later.]

Robin Bates: When did you realize that anthropogenic global warming (AGW) was a problem?

Dan Bloom: I was following the news about a warming world as far back as the 1970s and I even wrote a disaster novel in 1975, set in a flooded 2025 Manhattan. I sent the manuscript to New York literary agent, and one of his interns returned it with a note saying: "Interesting theme but your characters never come alive. Thanks for sending, though." I never tried my hand at writing a novel again, but it was a good learning curve and a good experience to get involved with the New York book industry.

Climate change caught my attention again when I was working at a Tokyo newspaper in the 1990s and we sent one of our reporters to Rio for the first big climate talks. His reports back to the paper made a big impression on me then. But I didn’t become personally involved until 2006. I was in Taiwan when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climage Change (IPCC) released a major report saying basically that if we don't clean up our act soon, then our goose was cooked. I became a bit depressed at first. Then, I found a way out of my funk and I knew I had to do something.

I got in touch by enail with James Lovelock, who had sat for an interview in The Financial Times about the Earth as a living organism. In a brief email exhange, Dr Lovelock encouraged me to raise the PR alarm about climate issues any way I could, and I have been blogging in a Lovelockian way ever since. The following year, I was encouraged when the New York Times DOT EARTH blog, run by veteran science reporter Andrew C. Revkin wrote a piece about my PR work on "polar cities.”

THE FULL INTERVIEW WILL APPEAR ON TUESDAY.]

REFERENCE

http://www.npr.org/2013/04/20/176713022/so-hot-right-now-has-climate-change-created-a-new-literary-genreREFERENCE

About Robin Bates

I have taught English since 1980, for a year at Morehouse College in Atlanta and then, since 1981, at St. Mary’s College of Maryland in St. Mary’s City, Maryland. I grew up surrounded by books in Sewanee, Tennessee, where my French professor father read to my three brothers and me every night of our childhood. When I had three sons of my own, I did the same, each night visiting Narnia, Middle Earth, Oz, Geatland, Camelot, Lilliput, 221B Baker Street, the Mississippi River, and other wondrous places.

This immersion in books has been vital to my life. When, as a 7th grader, I was one of the plaintiffs in a civil rights suit brought by white and black families against the Franklin County school system (for failing to comply with Brown vs. Board of Education), I drew strength from Huck’s friendship with Jim. As a lonely teenager in a military high school (and who of us is not lonely in those years?), I felt myself understood by existentialist writers such as Dostoyevsky, Sartre and Camus.

At Carleton College the poetry of D.H. Lawrence helped me get in touch with my love of life, including my sexuality.

Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, about a young man venturing into the world, was the key work for me after I graduated and entered the job market, working for two years as a journalist.

“Sonny’s Blues” by James Baldwin was important to me when I was earning my PhD at Emory University because of the way the older brother learns to get out of his head and enter his heart.

Works of literature have even come to the rescue at moments of unimaginable pain.

When my wife’s father died (he was a lifelong farmer), we read to Robert Frost’s “After Applepicking,” about a man lying down to sleep following a bountiful harvest.

When our oldest son died in a freak drowning accident, I turned to Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Neither made the trauma go away, nor did I expect them to, but they provided me some relief in picturing the grieving process as a journey, not as a mindless thrashing around.

Recently, as I watched a good friend wrestle with and finally succumb to an aggressive cancer, I found support in Gail Godwin’s novel The Good Husband, about the friendship between a woman who has lost a child and a woman who is dying of a malignant tumor.

Additionally, I have been privileged to see scores of students use literature to wrestle with their most profound issues, including divorce, heartbreak, identity crisis, and death. In teaching them how to use literature in this way, I see myself providing them with essential life skills.

No comments:

Post a Comment