在意大利的克雷莫纳

Benedicte Friedmann

45岁的法国小提琴家贝内迪克特-弗里德曼一直生活在法国。

在 "小提琴制造的摇篮 "里呆了大约20年。"来到克雷莫纳是--。

也许这样说有点自命不凡--就像走在最伟大的脚步上。

斯特拉迪瓦里、瓜奈里、阿玛蒂,"她说,"她指的是这座城市最令人尊敬的。

几个世纪以来的工匠。

"在这里做一名琴师,意味着可以百分之百地投入到乐器的创作中去,做得越多,你就会变得越好。"弗里德曼说。

弗里德曼说,在法国,为了赚取小提琴制作者的生活费,很多人都会做维修、重新梳理琴弓或销售配件,这让他们几乎没有时间从事艺术创作。

然而,对于克雷莫纳的小提琴制造商来说,情况并不总是简单的,他们在20世纪60-80年代享受增长,然后情况变得更加艰难。

"我们的市场,这是一个精英市场,已经萎缩了。我们正面临着一个非常严重的问题"。

工匠联合会主席乔治-格里萨莱斯说。

越来越少的演出和音乐场所,以及经验丰富的小提琴家更喜欢18和19世纪的古董乐器,都伤害了这个小众行业。甚至在COVID-19席卷意大利北部之前,格里萨莱斯就表示,"由于来自中国和东欧的无情竞争,这个行业陷入了困境。"

根据国际贸易中心的数据,中国是世界上最主要的弓形乐器生产国,去年出口额为7780万美元,即150万件乐器,超过世界市场的一半。

意大利排在第五位,出口额占世界出口额的4.6%,仅次于英国和德国,但高于法国。意大利的主要客户是日本和美国。

意大利的小提琴制造商必须与市场上的假琴竞争,有些假琴是在其他地方制造的,并标榜为克雷蒙尼琴,但最重要的是竞争来自于价格较低的小提琴。格里萨莱斯说,大师级的乐器起价为25000欧元(27943美元),尽管其他质量上乘的乐器售价可以低1万欧元左右。

不过,只要花200欧元或更少的钱,就可以买到一把中国小提琴、琴弓和琴盒。

巴洛克小提琴家法布里奇奥-隆戈说:"它们是经济型乐器,是系列化生产的,目的是为了那些初学的人"。

法国小提琴制作家弗里德曼说,小提琴的制作过程

n中国的大多数情况下,她和她的手艺有很大的不同。

克雷莫纳的其他人都在从事。

"它们是手工制作的,但10个小提琴制造商每天都在同一个零件上工作。这是一个生产线的工作,最后你得到一个组装,"弗里曼说。"没有独特性,没有真实性。"

在克雷莫纳,格里萨莱斯说,制作一把小提琴至少需要300个小时,也就是两到三个月的时间。

琴师们面临的另一个挑战是如何在克雷莫纳的竞争中脱颖而出。

弗里德曼说:"打响知名度有点费劲",而寻找订单 "是一个永久的追求"。

一些小提琴制造商通过在黑市上工作和避免高额税收,能够提供更低的价格--伤害了琴师同行。

尽管有这些挑战,弗里德曼说,集中在克雷莫纳的小提琴制造商创造了一个健康的环境,模仿和追求卓越的愿望。

"当有人问我哪把琴是我做过的最漂亮的琴时。

对我来说,它总是下一个,"Friedmann 说。

ENGLISH

https://www.taipeitimes.com/Ne

Violin maker Benedicte Friedmann tunes in to tradition

in Italy’s Cremona

Benedicte Friedmann, a 45-year-old violinkaker from France, has been living

in “the cradle of violin-making” for about 20 years. “Coming to Cremona was —

and maybe it’s a bit pretentious to say this — like walking in the footsteps of the greatest,

Stradivarius, Guarneri, Amati,” she said, referring to the city’s most revered

craftsmen of centuries past.

“Being a luthier here means being able to devote yourself 100 percent to creating instruments, and the more you do, the better you become,” Friedmann said.

In France, to earn a living as a violinmaker, many people do repairs, re-hair bows or sell accessories, which leaves them little time for their art, Friedmann said.

However, the situation is not always simple for the violinmakers of Cremona, who enjoyed growth in the 1960s-1980s, before things got tougher.

“Our market, which is an elite market, has shrunk. We are facing a very serious problem,”

said Giorgio Grisales, president of the artisans’ consortium.

Fewer performances and musical venues and the preference of seasoned violinists for antique instruments from the 18th and 19th centuries have hurt the niche industry. Even before COVID-19 swept through northern Italy, Grisales said that “the sector was in trouble because of ruthless competition from China and Eastern Europe.”

China is the world’s leading producer of bowed instruments with US$77.8 million in exports last year, or 1.5 million instruments, more than half of the world market, according to the International Trade Centre.

Italy is in fifth position, with 4.6 percent of world exports, behind the UK and Germany, but ahead of France. Italy’s main customers are Japan and the US.

Italian violinmakers must contend with counterfeit instruments in the marketplace, some built elsewhere and advertised as Cremonese, but above all competition comes from lower priced violins. Master instruments start at 25,000 euros (US$27,943), although others of fine quality can sell for about 10,000 euros less, Grisales said.

However, for 200 euros or less, it is possible to buy a Chinese violin, bow and case.

“They are economic instruments, made in series, and intended for those who are beginning to study,” baroque violinist Fabrizio Longo said.

Friedmann, the French violinmaker, said that the process of making a violin

n China is for the most part vastly different from the craftsmanship she and

others in Cremona engage in.

“They are handmade, but 10 violinmakers work every day on the same parts. It’s a line job and at the end you get an assembly,” Friemann said. “There’s no uniqueness, no authenticity.”

In Cremona, Grisales said that it takes at least 300 hours to make a violin, or between two to three months.

Another challenge for the luthiers is to stand out among the Cremonese competition.

“Getting known is a bit laborious,” while the search for orders “is a permanent quest,” Friedmann said.

Some violinmakers have been able to offer lower prices — hurting fellow luthiers — by working on the black market and avoiding high taxes.

Despite these challenges, Friedmann said that the concentration of violinmakers in Cremona creates a healthy environment of emulation and the desire to excel.

“When I’m asked which is the most beautiful instrument I’ve made,

for me it’s always the next one,” Friedmann said.

LINK in English: https://www.taipeitimes.com/Ne

With 160 studios in the city of 70,000 people, most of Cremona’s luthiers are foreigners, many of whom stayed on after studying at the International Violin Making School, which opened in 1938

Working in the shadow of the great masters, the violinmakers of Italy’s Cremona are valiantly fighting a shrinking market and foreign competition as they seek perfection, one violin at a time.

The birthplace of Stradivarius, Cremona is a veritable laboratory for luthiers from all over the world, where violin workshops seem to be everywhere you look.

Stefano Conia’s studio — just one of the 160 in the northern Italian city of 70,000 inhabitants — has not changed for decades.

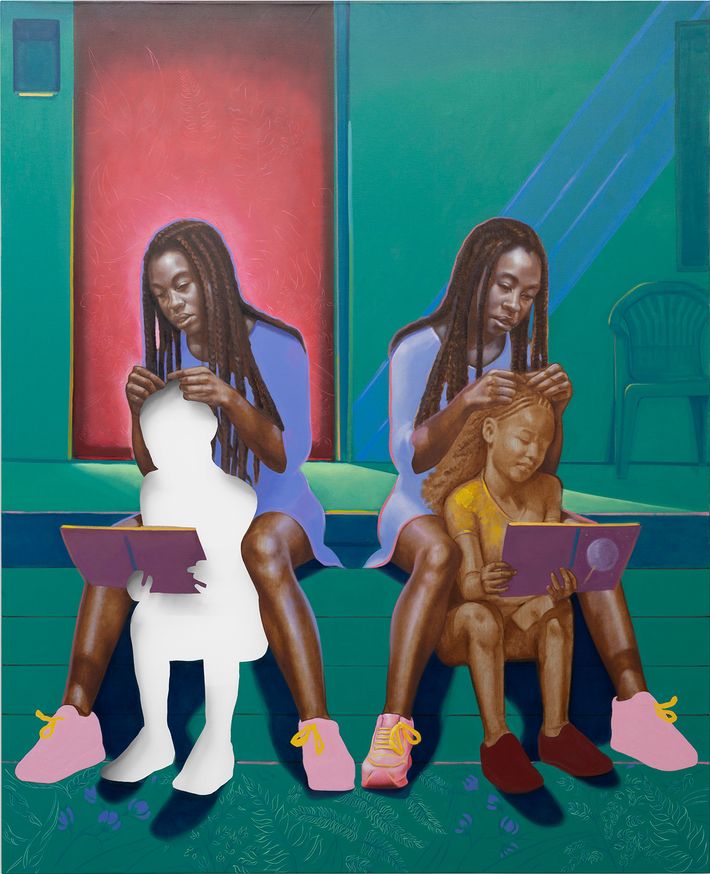

Stefano Conia, left, and his son, also named Stefano, inspect violins at their workshop in Cremona on June 9.

Photo: AFP

It is situated at the back of a flower-filled courtyard, and this native Hungarian, one of the doyens of Cremonese violinmakers, heads there every day, despite retiring nearly 10 years ago.

“If I stopped making violins, life for me would be over. Every day I’m here in the workshop. It’s an antidote to old age,” said a smiling Conia, 74, whose father crafted violins and whose son is also pursuing the family tradition.

Conia’s workbench faces that of his son’s. Both are covered with files, clamps, compasses, brushes and small saws. Wooden planks are laid on the floor.

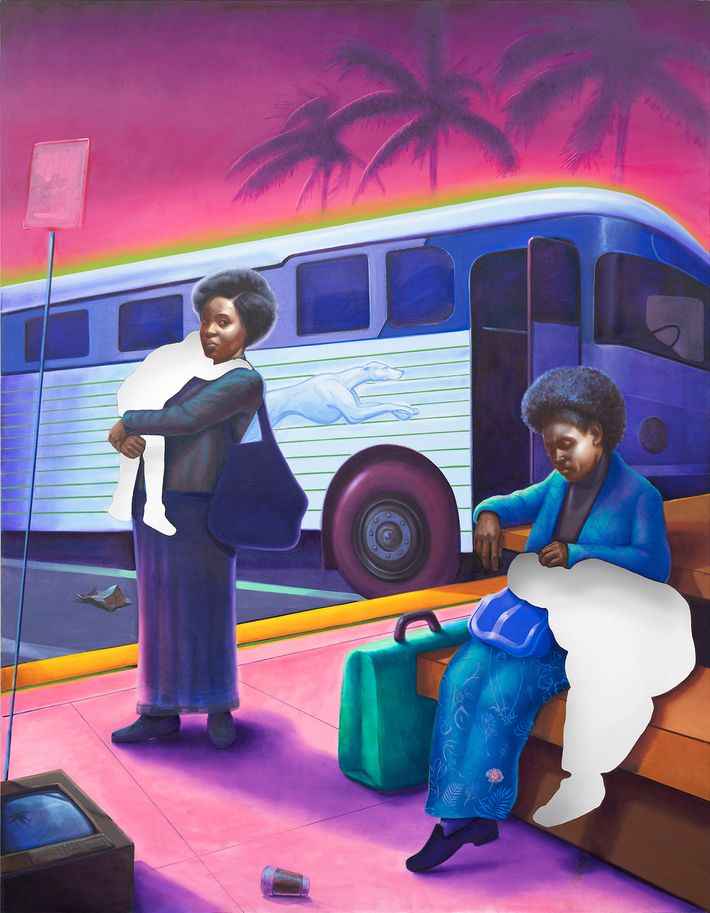

Violin body patterns hang in Stefano Conia’s workshop in Cremona on June 9.

Photo: AFP

“Going into violin-making was a natural choice,” said Conia’s son, Stefano, known as “the youngster” who began handling tools at the age of seven or eight.

He spent his childhood in the workshop his father opened in 1972, two months before his birth.

“I would play with the wood and the musicians would come and buy their violins and play,” said the younger Conia. “It’s always been a special atmosphere, which I really liked.”

For the Conias, the violins lovingly made from flamed maple or spruce are more than just instruments — they become family.

“The instruments are a bit like children. They live thanks to the energy we give them, it is a part of us that will continue to live after our death,” Stefano Conia said.

Like the Conias, the majority of Cremona’s luthiers are foreigners. Many came to study at the Cremona International Violin Making School and stayed on.

“The school was started in 1938, the first teachers were foreigners and the students come from all over the world. There is a saying that ‘Nobody is a prophet in his own country’ and it’s true that we, Cremonese violinmakers, are really few and far between,” said Marco Nolli, 55, one of this exclusive club.

Of the one-third of Cremona’s violinmakers who are Italian, only about 10 percent come from Cremona, he said.

Benedicte Friedmann, a 45-year-old from France, has been living in “the cradle of violin-making” for about 20 years. “Coming to Cremona was — and maybe it’s a bit pretentious to say this — like walking in the footsteps of the greatest, Stradivarius, Guarneri, Amati,” she said, referring to the city’s most revered craftsmen of centuries past.

“Being a luthier here means being able to devote yourself 100 percent to creating instruments, and the more you do, the better you become,” Friedmann said.

In France, to earn a living as a violinmaker, many people do repairs, re-hair bows or sell accessories, which leaves them little time for their art, she said.

However, the situation is not always simple for the violinmakers of Cremona, who enjoyed growth in the 1960s-1980s, before things got tougher.

“Our market, which is an elite market, has shrunk. We are facing a very serious problem,” said Giorgio Grisales, president of the artisans’ consortium.

Fewer performances and musical venues and the preference of seasoned violinists for antique instruments from the 18th and 19th centuries have hurt the niche industry. Even before COVID-19 swept through northern Italy, Grisales said that “the sector was in trouble because of ruthless competition from China and Eastern Europe.”

China is the world’s leading producer of bowed instruments with US$77.8 million in exports last year, or 1.5 million instruments, more than half of the world market, according to the International Trade Centre.

Italy is in fifth position, with 4.6 percent of world exports, behind the UK and Germany, but ahead of France. Italy’s main customers are Japan and the US.

Italian violinmakers must contend with counterfeit instruments in the marketplace, some built elsewhere and advertised as Cremonese, but above all competition comes from lower priced violins. Master instruments start at 25,000 euros (US$27,943), although others of fine quality can sell for about 10,000 euros less, Grisales said.

However, for 200 euros or less, it is possible to buy a Chinese violin, bow and case.

“They are economic instruments, made in series, and intended for those who are beginning to study,” baroque violinist Fabrizio Longo said.

Friedmann, the French violinmaker, said that the process of making a violin in China is for the most part vastly different from the craftsmanship she and others in Cremona engage in.

“They are handmade, but 10 violinmakers work every day on the same parts. It’s a line job and at the end you get an assembly,” she said. “There’s no uniqueness, no authenticity.”

In Cremona, Grisales said that it takes at least 300 hours to make a violin, or between two to three months.

Another challenge for the luthiers is to stand out among the Cremonese competition.

“Getting known is a bit laborious,” while the search for orders “is a permanent quest,” Friedmann said.

Some violinmakers have been able to offer lower prices — hurting fellow luthiers — by working on the black market and avoiding high taxes.

Despite these challenges, Friedmann said that the concentration of violinmakers in Cremona creates a healthy environment of emulation and the desire to excel.

“When I’m asked which is the most beautiful instrument I’ve made,

for me it’s always the next one,” she said.

FRENCH:

La luthière Benedicte Friedmann

se met au diapason de la tradition

dans la ville italienne de Crémone

Bénédicte Friedmann, une violoniste française de 45 ans, a vécu

dans "le berceau de la lutherie" depuis une vingtaine d'années. "Venir à Crémone, c'était -

et c'est peut-être un peu prétentieux de le dire - comme de marcher sur les traces des plus grands,

Stradivarius, Guarneri, Amati", a-t-elle déclaré, en faisant référence aux plus vénérés de la ville

artisans des siècles passés.

"Etre luthier ici, c'est pouvoir se consacrer à 100 % à la création d'instruments, et plus on en fait, mieux on se porte", a déclaré Friedmann.

En France, pour gagner leur vie en tant que luthier, beaucoup de gens font des réparations, recoiffent des archets ou vendent des accessoires, ce qui leur laisse peu de temps pour leur art, a déclaré M. Friedmann.

Cependant, la situation n'est pas toujours simple pour les luthiers de Crémone, qui ont connu une croissance dans les années 1960-1980, avant que les choses ne se durcissent.

"Notre marché, qui est un marché d'élite, s'est rétréci. Nous sommes confrontés à un problème très sérieux".

a déclaré Giorgio Grisales, président du consortium d'artisans.

La diminution du nombre de représentations et de lieux de musique et la préférence des violonistes chevronnés pour les instruments anciens des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles ont nui à cette industrie de niche. Avant même que COVID-19 ne s'étende au nord de l'Italie, M. Grisales a déclaré que "le secteur était en difficulté en raison de la concurrence impitoyable de la Chine et de l'Europe de l'Est".

La Chine est le premier producteur mondial d'instruments à archet avec 77,8 millions de dollars d'exportations l'année dernière, soit 1,5 million d'instruments, plus de la moitié du marché mondial, selon le Centre du commerce international.

L'Italie est en cinquième position, avec 4,6 % des exportations mondiales, derrière le Royaume-Uni et l'Allemagne, mais devant la France. Les principaux clients de l'Italie sont le Japon et les États-Unis.

Les luthiers italiens doivent faire face à des instruments contrefaits sur le marché, certains fabriqués ailleurs et annoncés comme étant de Crémone, mais la concurrence vient surtout des violons à bas prix. Les instruments de maître commencent à 25 000 euros (27 943 dollars US), mais d'autres de bonne qualité peuvent se vendre environ 10 000 euros de moins, a déclaré M. Grisales.

Toutefois, pour 200 euros ou moins, il est possible d'acheter un violon, un archet et un étui chinois.

"Ce sont des instruments économiques, fabriqués en série, et destinés à ceux qui commencent à étudier", a déclaré le violoniste baroque Fabrizio Longo.

Friedmann, le luthier français, a déclaré que le processus de fabrication d'un violon

n Chine est pour l'essentiel très différente de l'artisanat qu'elle et

d'autres personnes à Crémone s'engagent.

"Ils sont faits à la main, mais dix luthiers travaillent chaque jour sur les mêmes pièces. C'est un travail à la chaîne et à la fin, on obtient un assemblage", a déclaré M. Friemann. "Il n'y a pas d'unicité, pas d'authenticité."

À Crémone, Grisales a déclaré qu'il faut au moins 300 heures pour fabriquer un violon, soit deux à trois mois.

Un autre défi pour les luthiers est de se démarquer dans le concours de Crémone.

"Se faire connaître est un peu laborieux", alors que la recherche de commandes "est une quête permanente", a déclaré Friedmann.

Certains luthiers ont pu proposer des prix plus bas - ce qui a nui à leurs confrères - en travaillant au marché noir et en évitant des taxes élevées.

Malgré ces difficultés, M. Friedmann a déclaré que la concentration des luthiers à Crémone crée un environnement sain d'émulation et de désir d'exceller.

"Quand on me demande quel est le plus bel instrument que j'ai fabriqué,

Pour moi, c'est toujours la prochaine", a déclaré Friedmann.