UPDATE: When I asked Lydia Millet, if we could call THE LORAX an early example of ''cli-fi,'' she replied: "Sure thing!''

Dr. Seuss' The Lorax and Literature’s Moral Obligation and why, despite critics’ dismissal of activist-minded fiction, Lydia Millet believes that Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book is powerful because of its message, not in spite of it.

Lydia Millet on why ''cli-fi'' novels have a moral obligation to stand up and speak truth to a distracted world

Despite some literary critics’ dismissal of activist-minded fiction, Boston author Lydia Millet believes that Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book is powerful because of its message, not in spite of it.

REPEAT: Despite critics’ dismissal of activist-minded fiction, the author Lydia Millet believes that Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book is powerful because of its message, not in spite of it.

Despite critics’ dismissal of activist-minded fiction, the author Lydia Millet believes that Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book is powerful because of its message, not in spite of it.

In a conversation for this series, Millet discussed The Lorax, Dr. Seuss’s personal favorite among his books, an overtly environmentalist fable that also manages to tell a haunting truth about the destructive power of greed. Maybe the Lorax—that bossy, pedantic guilt-tripper—fails to deliver a convincing message, but the book succeeds where the character fails. We discussed how writers can embrace activism without compromising artistry, and what it means to build a compelling moral vision.

The narrator of Sweet Lamb of Heaven leaves her controlling, menacing husband, fleeing with her infant daughter all the way from Alaska to coastal Maine. She’s also hearing voices: Strange messages and mystic pronouncements fill her ears, though only when her daughter is awake. She isn’t crazy—this character coldly and clinically researches her symptoms, and consults doctors who say nothing is wrong. But she knows something isn’t right, either, as her conviction grows that her husband will stop at nothing to find her.

Lydia Millet: You remember the Lorax. Not the Lorax of movies—he’s only a distant cousin—but the original Lorax of paper and ink. He was a Dr. Seuss creature, a fanciful animal-person who was “shortish and oldish and brownish and mossy,” and talked in a voice that was “sharpish and bossy”—in short, an environmentalist. As a writer who’s been working with activists for 20 years now, I’ve met a lot of Loraxes.

We were a Seuss family. As a child I read almost all of his books, but the one I loved best was The Lorax. It’s a fairy tale of failure—the shade of defeat and the shine of hope. All of us who came up with the Lorax (I was born three years before he was) were raised on a tragic fail. The story goes like this: In a dismal blue-and-brown landscape, a small boy seeks out a tale-teller who lives alone in a shabby tower—a tale-teller whose face we never see. In exchange for some whimsical tokens dropped into a pail, the hermit tells his story. This is the aging Once-ler, who came to a beautiful place when he was young and turned it into a wasteland. He chopped down its lovely grove of Truffula trees to make thneeds, “which everyone, everyone, everyone needs.” He drove out the bears and the birds and the fish, ignoring the Lorax’s angry warnings. And when the last tree fell to the axe, and the factory shuttered, the Lorax left too, lifted away through a hole in the smog. Only the Once-ler remained in the promised land he’d destroyed. And a dilapidated sign that read: “The Street of the Lifted Lorax.”

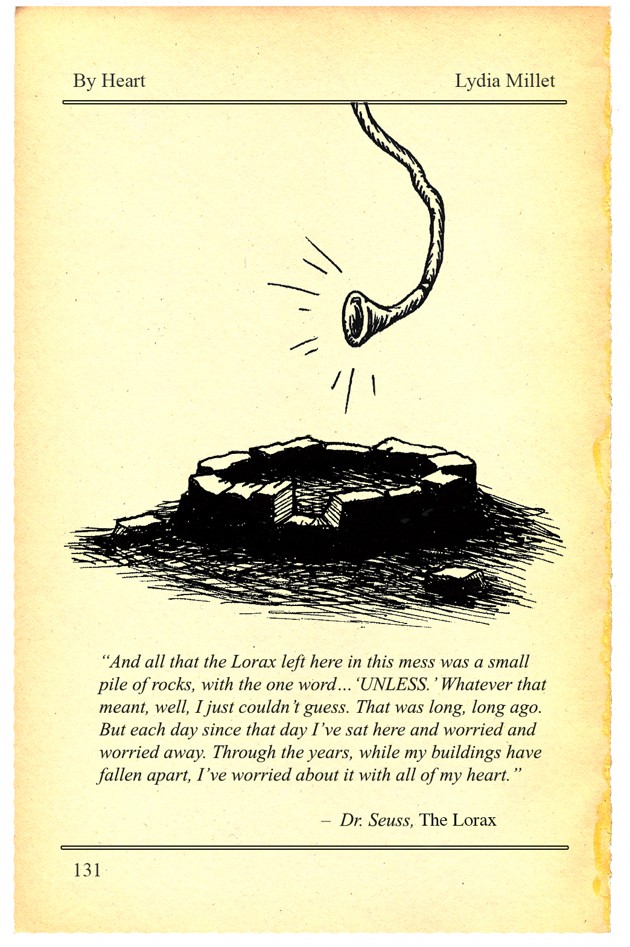

One of my favorite verses comes near the end of the book:

And all that the Lorax left here in this mess was a small pile of rocks, with the one word … ‘UNLESS.’ Whatever that meant, well, I just couldn’t guess. That was long, long ago. But each day since that day I’ve sat here and worried and worried away. Through the years, while my buildings have fallen apart, I’ve worried about it with all of my heart.I admire this passage for its succinctness of nostalgia and remorse, its simple and straightforward assertion of the phantoms of possibility and powerlessness alongside each other. I’ve wanted, in much of my own fiction, to echo this child’s parable, call forth a ghostly Lorax and adult unless: a gesture of momentum, in the context of story and interior monologue, that entertains the necessity of a continued presence in the world of forests and pupfish and elephants, not only for their own sake but for ours.

Isn’t that a subject worthy of novels? Shouldn’t the cascades of extinction and rapid planetary warming register in our literature? And yet, despite the fact that most Americans support the work of saving species from winking out, and increasingly support strong action to curb climate change, the highly rational push for the preservation of nature and life-support systems often appears in the media—and certainly appears in most current fiction—as a boutique agenda. Climate change is shifting that marginalization, but not fast enough.

Advertisement

But I happen to believe in the urgency of now. I don’t accept the proposition that ours is a historical moment like any other, that we can handily shrug off our duty to the future by placing ourselves in an endless, linear continuum of progress that makes its share of errors but is finally, comfortingly self-correcting. Rather I follow the strong evidence for the singularity of this human era, its unique power to make or break that future, directly linked to tipping points associated with climate catastrophe and the irreversibility of extinction. I cleave to science and the need to communicate science, or at least the products of science. Beyond and within science, love: not the love we have for ourselves, but that greater love we forget or take for granted in daily life, the love of otherness. The desperate need for otherness. And I suspect there’s no place, in art or journalism or politics, that isn’t ripe for that discussion.

I rarely write a book where I’m not trying to approach some idea or set of ideas that I think is of interest in the cultural moment. Some of my books touch on the loss of animal and plant life and what that means to people; my new novel, Sweet Lamb of Heaven, is partly about the use of religious belief in politics and the intersection of that use with the diminishment of diversity, cultural and linguistic as well as biological. In approaching these ideas in a fictional vein I’ve had to wrestle, on the technical side, with the trickiness of balancing the aesthetics of contemporary writing (grounded in the subjective and averse to the didactic, committed to the personal and hostile to the general) with what might unfashionably be called a moral vision.

There are a few ways to know whether something I’ve written succeeds in achieving this balance, the tension of being properly subjective yet also conveying a more expansive sense of right and wrong. If I find myself repelled by the text, pulling away from something that’s meant to be read philosophically, that’s a good sign that someone else will feel that way, too. In fiction, philosophical, political, or religious ideas tend to be most convincing when they arise organically out of a character. And the only way I know how to make characters is by voice, the texture of personality inside a narrative. If you can establish a voice that can get away with being somewhat abstract, that’s part of the battle. And part of it is simple charisma.

It’s also about pulling back and allowing ambiguity—enough that the reader can decide his or her own relationship to what’s being encountered. You have to establish a certain authority for the reader to suspend disbelief, but there’s great fluidity in fiction: You don’t need to be representing your own position, indeed you don’t need to be representing any real position. You’re not a historian and you’re not a journalist. You can write whatever you want, however you want, and it can be read however the reader wants to read it.

That’s the risk and the excitement. Two private minds in conversation.

We shouldn’t forget that literary fiction is part of the now, part of social discourse. It’s not a medium for polemics, but it is clearly a medium for speculation. And for the examination of collective choices as well as individual.

This is nothing new; it goes back well before Dickens or Hardy or Eliot.

My feeling is that the struggle to write well is also the struggle to write honestly, even when they seem to be at loggerheads. And that candor—elusive and sometimes rudely naked—shouldn’t be just the easy honesty of me but a more ambitious honesty of us. Not the sole purview of children’s books, but the purview of any book at all.

In the end, I think a bit of shamelessness is called for.

No comments:

Post a Comment