NEWS ALERT! "The Australian" Dec. 6 - by Fiona Harari - HEADLINE: " The Tattooist of Auschwitz is distorting, Holocaust historians say'' https://northwardho.blogspot.com/2018/12/scanned-pages-1-and-2-from-australian.html

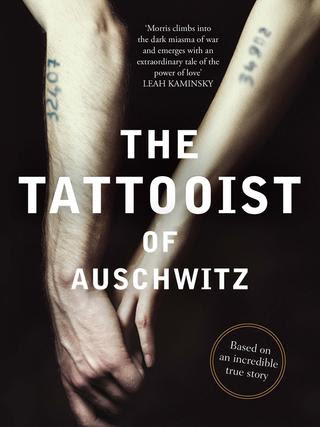

Controversy indelibly inked on World War II Holocaust love tale

PHOTO: Mum Gita, little Gary, and father Lali in the 1960s in Melbourne

reported for THE AUSTRALIAN newspaper by veteran Australian journalist Caroline Overington

''The Tattooist of Auschwitz'' is ‘based on a so-called true story’, but given that it’s a sex and romance Holocaust novel based on a big fat white lie, does it really matter if there’s a few whoppers, tall tales and outright mistakes? Yes, it does!

============================================

He pushed the Nazi-engineered needle machine into her arm, starting the process of tattooing a number that would forever identify her as a Jew, and as a prisoner of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Although it was not her first tattoo. In fact, he was asked to re-do an old tattoo that was wearing off. So he was a re-do man, a make-over man.

As the tattooist in the camps, he had of course done something similar a thousand times before, but this was different. He felt it, as the needle went in; she felt it, too.

In the process of inking her arm, he had fallen in love.

This, as devoted readers around the world will know, is the pivotal, as well as the opening scene in The Tattooist of Auschwitz by debut Melbourne screenwriter-novelist Heather Morris, 70, who is not Jewish and admits she doesn't know much about Jewish history or the Holocaust, having grown up as a child in small rural New Zealand town where there were no Jews, at least she says she never met one until she moved to Australia as an adult.

The controversial novel tells the alleged story of a real-life tätowierer, or tattooist, one of a team of tattooists in the camp and not the only one in Auschwitz, the late Ludwig (or Lale, or perhaps Lali?) Sokolov, and his wife, Gita (nee Furman) who allegedly met in the Nazi concentration camp during the war, and allegedly became torrid and sexually hot lovers inside the camp, often making X-rated love in full view of the Nazi guards, while both were prisoners in the Nazi camp.

The couple survived the Holocaust, married and later moved to Melbourne, Australia, where they had a son, Gary, now 60. Now both Lali and Gita are long dead, and their love story, or at least the telling of it in fiction form, by a previously unknown non-Jewish Melbourne writer, is generating some heated controversy in literary circles worldwide, from The New York Times to the Times of Israel blog website and the San Diego Jewish World newspaper edited by Don Harrison.

The Tattooist of Auschwitz is said its editor and publisher in marketing material and on front cover of the book itself to be allegedly “based on a true story”, but how much of this book is real, and how much is imagined?

Given that it’s a novel, does it matter if there are few mistakes, mis-steps, big fat white lies or outright falsehoods? Yes, it does matter and time will tell just where truth really does lie.

Also, what if any obligation does Heather Morris have to her subject’s family, in particular to Gary Sokolov — a child of Holocaust survivors — and his three children born in Melbourne?

The two sides -- Morris (and her publisher )and the Sokolov family -- were once close, but now they are dealing with what Morris describes as “issues”, some of which are believed to be about their confidential financial agreement drawn up before the book took off. So now you see, the old canard, Jews and money. Well done, Heather, well done.

''The Tattooist of Auschwitz'' is this year’s global publishing sensation. It has over 1 million copies in print now. According to figures supplied by Nielsen BookScan, the book is Australia’s Number 1 fiction title over the first nine months of the year, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. It is also No. 1 on the paperback fiction bestseller lists in Britain and in the USA, and the TV rights, for a mini-series to be shown globally to coincide with the 75th anniversary in 2020 of the liberation of the camps, have been sold as well, with a Jewish-Australian screenwriter hired to write the script.

Morris says Gary Sokolov started out supporting the book but had “backed away a bit”.

“I can understand that,” she says. “It must be difficult, having your family’s story out there in a big way all of a sudden, and yes, there’s been a few issues, but I don’t think it’s Gary; I think it’s his wife. The Jewish wife canard. A shrew if there ever was one! She’s become fixated on what she says are ''some'' mistakes, but I’ve said from the start, all I’m doing is telling the story that Lali allegedly told me and if I manipulated some of his memories and recollections to fit my idea of a marketable screenplay for a movie. so what?"

“It’s not a memoir. It’s fiction, and if people want to quibble, fine, you’ll always get that.” The Sokolovs, neither Gary nor his wife, did not respond to this newspaper's requests for comment.

There is no question that Morris displayed remarkable patience and persistence in bringing Sokolov’s story to the public’s attention, as did her very naive and young non-Jewish editor and publisher, Angela Meyer, from Echo Press. “This is a great story, because it’s about a little book that we believed in, that has become a huge success,” Meyer, who refuses to respond directly to her Jewish critics overseas and blocks them on Twitter to keep them at bay, says, “and especially because I came across it when I was still pretty new to the job, so this has been incredible for me, too.”

Before discovering The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Meyer had been “a book reviewer, a blogger, I’d worked in a bar” and she had been busy writing her own, well-reviewed debut, A Superior Spectre. But she hadn’t been getting many pitches for her own novel from literary agents, “so I was trying to be creative about ways to find great new books”.

She decided to have a look on Kickstarter, which is like a GoFundMe for people who want to start creative projects. There she found Morris, who was at the time trying to raise money to self-publish “this amazing story”. “We met, we had a coffee,” and Meyer immediately felt “tingles up my arms, all over my body, really”. “I mean: what a story,” she says.

Morris says she came across Lali’s story almost by accident. “I had always wanted to write a screenplays, for TV or Hollywood, except I had all these other responsibilities: I was married, we had three kids, I worked for 21 years in the social work department at the Monash Medical Center. In the canteen one day, a friend told me that she had a friend, the son of a Holocaust survivor living in Australia, Gary Sokolov, who was looking for somebody to write his father’s story.”

She went to meet the man she calls Lali, and they became friends. “At this point, his wife Gita had only just died, and she had never wanted Lali to talk about what they’d been through in the camps,” Morris says, “but he was 87, and he kept saying he really wanted to hurry up and join Gita in heaven, if there is a heaven for Jews who do not accept Jesus as the son of God, but he wanted somebody to tell his story first.”

She says she told him: “You know I’m not Jewish?”

“And he said, good, he didn’t want a Jewish writer. He didn’t want anyone with any ethnic or religious baggage, or Holocaust family history. I told him, I don’t think I even met a Jewish person growing up (in a small town in New Zealand, before moving to Australia at age 18) or not to my knowledge.”

Morris frankly admits she didn’t know much about the Holocaust, either. She hadn’t read Elie Wiesel, or Viktor Frankl, or Primo Levi, or Martin Gilbert. She had seen Schindler’s List, at the movies, “and that’s how I saw Lali’s story, as a Hollywood movie. Lali even told me that he envisioned several famous Hollywood actors to play him and his wife in the movie, if it was ever made.''

She wrote a screenplay allegedly based on his life, and their wild sex and romanatic love story, and it got optioned by some screenplay contests, not once but twice, but those options lapsed, twice, over a ten year period. “I was losing hope,” Morris says, “but even on Lali’s death bed, I was saying to him: I will never stop trying to tell your story.”

Lali died, aged 90, in 2006.

Meyer says she knew deep down in her heart that the book would be a success, “because we’d have a meeting about it at work, and all the Australian women in my office would be crying”. She says they discussed writing The Tattooist of Auschwitz as a ''memoir,'' but Morris says she wanted it to be ''fiction.''

In the year since it was published in 2017, some Jewish readers and Holocaust historians at the @AuschwitzMuseum in Poland have come forward, complaining about inaccuracies. For example, Morris writes — not once, but 3 times in the book — that the number that Lali tattooed on Gita’s arm was ''34902.''

Holocaust historians and Jewish educcators say that a woman who entered Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1942 would have received a four-digit number, and there is some evidence for that, including from Gita herself.

Like thousands of Holocaust survivors from around the world, both Gita and Lali Sokolov agreed in the late 1990s to give oral testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation.

Their tapes can be viewed only in person, at places such as Yad Vashem in Israel, at the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin and at the Sydney Holocaust Museum.

Gita was interviewed by researcher Nick Fischer in Melbourne on January 30, 1997. The two-hour-long tape shows her talking about being transported to Auschwitz, where she was stripped of all her possessions, and shorn of her hair.

She is asked: “Did you have a number?”

In a loud, clear voice, she replies “4562” — which obviously is quite different from 34902.

Morris says she “wrote down what Lali told me”.

“Since the book came out, I’ve heard that the number in the book can’t be her number, that she had a four-digit number, but I’m not writing the official history, I’m writing Lali’s story, and that is what he told me, or what I maybe unintentionally manipulated him into saying, that he tattooed her with that number, so it could be that he tattooed her a second time,” she says. "Then again, he was an old man when I met him and maybe he was making some things up just to please me and get the screenplay made into a Hollywood movie."

Some Jewish readers have questioned whether the tattooing of Gita by Lali ever happened, but Gita leaves no doubt that it was Lali who tattooed his lover.

On the Shoah tape, Gita says: “And do you know who made it (my number)? My husband. He was the Tätowierer.”

Gita in old age, before she died, later had her tattoo erased from her skin for reasons unknown.

Here is a key part of the controversy: The couple don’t say on their tapes that they fell in love when Lali allegedly tattattoed her with a tattooist's needle. In fact, in the second hour of her interview, Gita says of Lali: “I knew him, but not when he made my number, but later on, somehow.”

Lali, who was interviewed on December 5, 1996, says: “I saw her marching one day, a very beautiful girl (with a) red little thing (probably a scarf) on her head … she saw me, and somehow we started [falling in love].”

A Nazi guard offered to deliver letters from Lali to Gita, which he then began writing, as per the book.

Morris says: “You have to remember how much they protected each other. He told me that he remembered the moment very clearly.”

Gita in her taped interview confirms many of the other stories in Morris’s book, including the dubious final scene, where he allegedly turns up on a horse to find her in Bratislava after the war. For most readers, that scence is total nonsense, romantic silliness. But hey, it's make for great PR material and the newspapers and magazines ate it up without ever questioning the publisher for not vetting the novel better.

The novel ends with an ''afterword'' by Gary Sokolov, who has previously expressed gratitude to Morris for bringing his father’s story to life. Morris thanks him in the acknowledgments, saying: “You have my gratitude and love always for allowing me into your father’s life and supporting me 100 per cent in the telling of your parents’ incredible story.”

Now they disagree even over the spelling of his father’s name.

“Gary’s Jewish wife found a piece of paper that Lali had written on, one sentence, and she reckons the way he spelt his name, it’s an ‘i’ on the end, and now she’s fixated on this,” Morris, who perhaps deep down her New Zealand/Australian psyche may harbor some antisemitic sentiments herself, as many white people in Australia do, even the reporter Caroline Overington herself, who on Twitter in 2009 said some pretty nasty jokes about Jews and gassing them in the Nazi ovens, ...

“My response has been, this is an 80-plus-year-old, it’s shaky writing, and anyway, Lali read my screenplay, with the name L-A-L-E. That is what he told me his name was.”

In the USA version of the book, his name will be spelt Lali. It will also print the correct number of her tattoo before she later had it removed in old age in Australia.

Of the various controversies, Meyer says: “With a big popular Oprah-style New Age success there will always be other things that will come out of the woodwork, especially from Jewish readers and Polish scholars the Auschwitz Museum in Poland, but on the whole it’s a book that has moved so many people and made such a positive impact and I’m so proud of what the book has become. If some critics all it a Holocaust literary hoax, as one Jewish blogger has been doing, that's his problem.”

Morris agrees. She visited Auschwitz for the first time in 2018. “It was interesting,” she says, “because I walked down the corridor, I knew, the men’s camp would be there, the rooms for the gypsies there, it was exactly as he had described it. Exactly. And telling his story has meant that I have been able to tell the Holocaust story to a new generation of gullible readers who don't the difference between fact and fiction, and don't really care. All they want is a good cry, and I delivered the goods.”

Gary Sokolov

Gary Sokolov