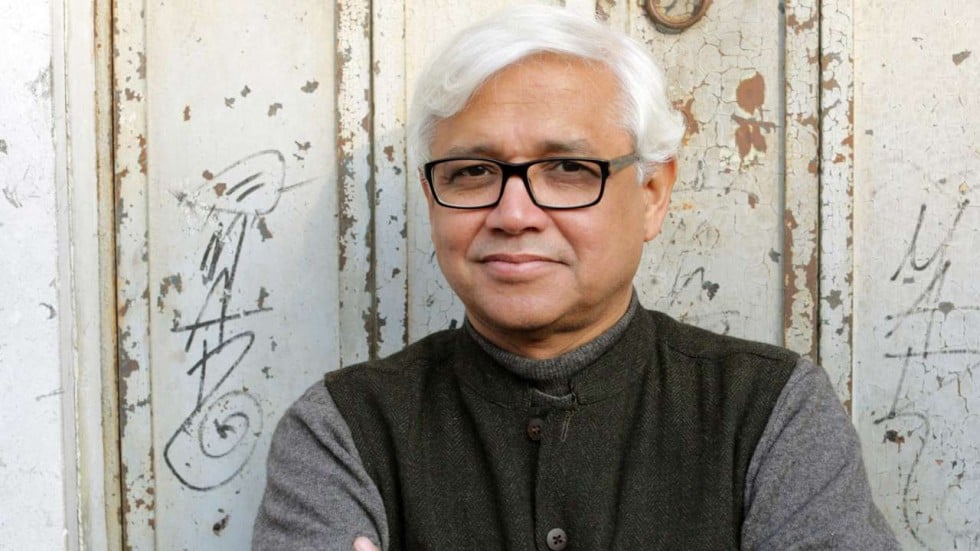

Indian essayist Amitav Ghosh pierces silence about looming climate-change catastrophe

Indian essayist Amitav Ghosh pierces silence about the looming climate-change Climapocalypse and calls for more cli-fi novels and movies as in the West now

Ghosh, whose latest book is The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, says politics-as-usual is a great distraction from an ‘absolutely terrifying’ subject

PUBLISHED : Friday, 22 July, 2016, 11:01am

UPDATED : Friday, 22 July, 2016, 11:01am

Indian writer Amitav Ghosh’s latest book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, is an extended essay of sorts on climate change, the catastrophe unfolding around us and the conspiracy of silence around the dangers of it. During a recent visit to New Delhi he spoke to Elizabeth Kuruvilla

Evidently you follow the climate change phenomenon quite intensely.

Yes, I do follow the actual climate change impact very closely, the scientific findings, what we see unfolding around us. And actually, even though climate science is a very advanced and complex science, it’s not conceptually as difficult as, say, string theory is.

While cities worldwide work together against global warming, Hong Kong stands aside

Climate science is based largely on empirical findings so anybody, even a layman, can understand that an ice-free Arctic is going to be a very serious development. We just don’t really realise the extent of the changes around us.

The changes don’t happen uniformly around the planet; they are concentrated on certain places.

There’s a sense of futility, hopelessness in your book.

The 20th century was this great carbon-fuelled party. And we arrived at that party very late. So, in a sense, we are still in party mode. Most of us, the Indians, Chinese, we Asians, we arrived at this party late, so we want it to go on. So I suppose we just aren’t looking at the reality, which is that this party is now on its last legs. That there are natural limits in this world which won’t allow it to continue.

The Great Derangement.

You believe writers have a moral responsibility to write about climate change?

I certainly would never place myself in a position where I’m telling other writers what to write about. What I’m reflecting on is writers today do respond to the circumstances around them, to political circumstances. I mean, how many books do you see which talk about, say, terror, or 9/11, or things like that? So the question for me becomes really, why is it writers who are very aware of what’s happening in the world around them are unable to write about this one phenomenon which is actually a meta-phenomenon, within which every other phenomenon is encased? [BUT I KNOW THAT MANY CLI-FI NOVELS IN THE WEST DO EXIST NOW SO I AM NOT COMPLETELY RIGHT ON THIS.] See cli-fi.net

Take the case of Indian fiction. I mean, so much is now written about so many political subjects. Writers are really proud of being political; they are constantly getting involved in politics in one way or the other. And yet, this thing, which is perhaps much more important than any day-to-day politics, they are completely, as it were, indifferent to.

As you write, they are, in a sense, complicit in the silence around climate change.

You could say that in fact what we have come to think about as politics is, in a sense, actually a great distraction from all that is really important in the world. That’s really become my feeling about what we call politics today, which is that it is really just a form of entertainment that is completely complicit with industry and a certain kind of economic structure. Just think about it – we’ve always historically been a water-stressed area. Water is what life depends on. So historically, in India and China, any state structure, its first duty was to provide water, to plan for water. If you go to any water-stressed part of India, say the Deccan or Tamil Nadu, all of history we see that there is this enormous effort dedicated to maintaining tanks, to keeping irrigation systems going, to maintaining this entire hydrological structure, which is actually an artificial structure.

The aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey. Ghosh says those who have suffered from extreme events like this are actually less willing to make the connections he has. He recommends reading Nathaniel Rich's cli-fi novel about Hurrican Sandy titled ODDS AGAINST TOMORROW. see cli-fi.net

So how should we address the issue?

That’s for experts to address and I’m not an expert. But certain things are clear to me. We can’t in any way address this issue until we address the causes of it. Which is the economic model we’re now pursuing, a model that is solely oriented towards perpetual growth. That is the first issue that we have to confront. That we can’t carry on living as though everybody can expand their carbon footprint or their energy footprint. If you don’t acknowledge that, how can you even begin to have a serious conversation about this? And that is exactly what this document is about. It is about perpetual growth.

It’s just trying to find the different means of perpetual growth.

Your book is terrifying to read. Following climate change as closely as you obviously do, how can you not be paranoid?

If you follow the stuff, it is absolutely terrifying. And you know many of the scientists who deal with this stuff are deeply … I mean, there is this whole phenomenon known as climate despair. They are depressed just seeing what is happening in the world. Somehow, this denial phenomenon, there have been many studies of it, it’s strongest among those who are actually affected.

Say, after Hurricane Sandy, they did a study and they found that the people who actually lost their homes, they didn’t want to talk about climate change. They wouldn’t recognise the link, they didn’t want to acknowledge it. I think it is particularly American, that phenomenon, because in America this phenomenon has become very politicised, it has become an identity issue. What identity has to do with it, I can’t figure out. So that’s why people don’t want to think about it or address it.

1 comment:

17/ 34

Post a Comment