Al Gore, climate change activist out to save world, likens himself to Jackie Robinson

Al Gore says he’s the Jackie Robinson of global warming, and says he’s spearheading how people view the climate just as Robinson did for civil rights.

In a revealing interview published on Sunday, Al Gore told The Tennessean newspaper that he considers himself to be like Jackie Robinson, the famous baseball player that received a torrent of abuse for playing on an all-white baseball team in the 1940s. When asked if there were any similarities between Robinson’s efforts to integrate big-league baseball and his crusade to bring a climate change message to the masses, Gore said there were definite parallels. America’s largest civil rights movement, he believes, was analogous to climate change when there was still a long way to go.

The Tennessean reporter who interviewed Gore asked about the politics of the climate change debate, and why Gore has subjected himself to such harsh political abuse—the same treatment that Robinson received in baseball. But Gore, who could have simply said that comparing himself to a civil rights champion would be a disservice to the African-American community, was unable to pass up the chance to get an extra heaping of hubris with a side order of self-importance. And hold the humility, please.

But fear not, Gore understands that this is part and parcel of being Earth’s number one diplomat. Like Robinson, who was considered a civil rights pioneer during one of America’s uglier eras, Gore believes just as adamantly he is also faced with a huge undertaking: saving mankind. Admitting in the interview that his climate change rhetoric may sound a bit over-the-top, he still thinks it’s correct to describe what he does as a “mission.” Gore says that it was his privilege to have a job that requires “every ounce of energy” he could muster into changing the world, as his self-written message dictates.

Gore said there is only one person with a more persuasive message than himself: Mother Nature. But he believes she’s on his side, and is his most powerful ally.

===============================

However, it wasn’t until he gave his presentation on the deck of a houseboat on Center Hill Lake that he realized the impact it might have on the public at large.

Even then, the 45th vice president of the United States never imagined the “fancy version” of his three-carousel slideshow would be developed into an Oscar-winning documentary film, "An Inconvenient Truth," or that a No. 1 bestselling book of the same name, which was released May 26, 2006, would lead to his winning the Nobel Peace Prize a year later.

With his dog, Bojangles, at his side, Gore, 68, a former reporter for The Tennessean, spoke with his hometown newspaper about the environment and climate changes on the 10th anniversary of "An Inconvenient Truth."

Does it feel like it’s been 10 years?

It really doesn’t. When I look at all the progress over the last 10 years, it sometimes makes me feel that it’s been longer than that, but emotionally, it feels like it was just a short time ago.

How good do you feel about the past 10 years?

Well, we’re far from where we need to be, so there is certainly no room for celebration, but I feel a sense of joy that we’ve made a lot more progress than many thought was possible.

The overwhelming majority of Americans in both parties and independents now agree that the climate crisis is real, man-made and must be dealt with, so that’s a lot of progress, and worldwide, every country in the world — just about — signed onto the Paris agreement and business of progress has been even more impressive in many ways than what’s happened in the policy world.

In the first three months of this year, 99 percent of all of the new electricity generation was solar and wind. Virtually no new gas or coal. Worldwide, last year, if you look at all of the new electricity generation built, 90 percent of it was solar and wind and renewables. The rapid reduction of the cost of electricity from solar photovoltaics and wind energy have astonished people all over the world. In many areas, it is now much cheaper to make electricity from sun and wind than it is from coal or gas, and that’s driving a dramatic change in business and in industry.

Nevertheless, we’re still putting 110 million tons of global warming pollution into the atmosphere every day. And it’s adding up. The cumulative amount of heat energy trapped by all the man-made pollution up there is now equal to 400,000 Hiroshima-class (atomic) bombs going off every day.

That’s disrupting weather patterns, putting a lot more water vapor into the air and causing record downpours — like the ones going on in Texas (recently) and in France and Germany and other places. And, simultaneously, it’s causing these droughts because it’s pulling the soil moisture out of the land, so with the ice melting and sea levels rising — as the scientists predicted — tropical diseases like Zika are coming into areas like the U.S.

The public’s concern has now reached the levels that the politicians almost have to do something about it.

We can both admit that science is not a favorite subject for most people, so is your gift the ability to take all that information you just shared and articulate in a way that’s understandable for the common person, who isn’t as familiar with the topic?

I had a wonderful experience when I was younger in getting to know a lot of the leading climate scientists and, over the years, they have been good friends and patient enough to explain things in simple terms to me over and over again until I could get into language that was understandable to me, which I could then use to communicate what they were saying to a general audience.

I always go back to the scientists and say, "OK, here’s how I’m going to put this. Is this accurate?" And inevitably they’ll say, "You need to tweak it here and you need to tweak it there." I give them the credit for whatever I’ve been able to get across to the general audience with the movie 10 years ago and the books I’ve written then and since.

How did the movie allow you to build on (the slideshow), and was the book a way to build on the movie?

The first slideshow that I gave was back in the late ’80s and I had been giving speeches and presentations — before I built a slideshow — with flip-up charts and graphs. But I found a great guy at the National Geographic Institution, who gave me access to their picture file and helped me find some people who could help me build some graphics.

That first slideshow was on a Kodak slide carousel, and I kept developing it to the point where I had a fancy version that had three projectors — each with its own carousel and one screen. They would fade in as the other one was fading out.

And that was believed to be high-tech.

I thought that was the cat’s meow (laughs). Then, about 10 or 12 years after that, I switched over to an Apple Macintosh and learned how to operate their program called Keynote, and when the slides got digitized, they were a whole lot easier to deal with.

You no longer had to worry about the slides being backward.

I remember one time, down at MTSU, I was showing one of the carousel versions and two or three of them upside down and backwards and it was very embarrassing because you have to stop and it’s just an ordeal.

But, anyway, when I finally got it on the computer, I was able to update it more quickly, refine it more quickly, put new images in more quickly, and this was a time when the climate science was moving very quickly.

The first time I really had the feeling that I was really going to be able to make a difference with that slideshow — long before the movie — was one Saturday night on the front end of a houseboat on Center Hill Lake where a whole gang of my rowdy friends from Smith and DeKalb and White (counties) were up there, and we were drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon and one thing led to another and I gave my slideshow on the deck of that houseboat.

I knew the gang well enough to know their reactions were not to make me feel nice about it. They really were impacted by it. I won’t quote the comments because it’s a family newspaper, but that’s the way we talk sometimes.

After that, I thought, I need to start taking this out more to a broader audience, so I started giving the slideshow a lot more frequently to basically anybody who would sit still for it, and that’s when some people in the movie industry saw it and wanted a meeting with me to say it ought to be made into a movie. I actually thought that was not a good idea.

And Davis (Guggenheim), who directed it, didn’t initially think it was a good idea.

Yeah. I’m glad he didn’t tell me that then because he was part of the gang trying to convince me to do it, but they finally got through my thick head that they knew more about making movies than I could ever imagine and that there was a way to make it into a movie. That’s how that all came about.

I put together the book version of the movie at the same time they were finishing up the movie and, basically, the slides that were in the movie make up the backbone of the book and they came out at the same time. They kind of worked together in a way that I didn’t appreciate at the time, but people who would read the book would go see the movie and people who saw the movie would buy the book. I gave all the profits to the Climate Reality Project.

I don’t want to compare you to Jackie Robinson, but I’m going to draw a parallel. When you’re first at something or, in your case, out front, it’s often difficult. You had naysayers. Even though you were at the top of the New York Times bestseller list, there were people who made fun of it.

Oh, yeah. A few still do.

How do you deal with that? How are you able to keep putting yourself out there? How do you emotionally tell yourself, "It’s worth it?"

There is a time-honored tradition of people who strongly disagree with a message and take it out on the messenger, and opponents of integration had a personal animus for Jackie Robinson. Opponents of all the great social movements would take out after the advocates that were most effective in asking people to change.

As a result, I don’t take it personally when the criticism comes at me. I believe so passionately in this mission, if you will. The word "mission" might sound a little grandiose, but that’s kind of what it feels like to me. Honestly, it is a joy and a privilege to have work that justifies pouring every ounce of energy you can pour into it. That is a blessing that is to be cherished.

Speaking of naysayers, they always point to the fact that the Earth is millions of years old, so how do you go about convincing people to have a sense of urgency?

That’s a question that I ask myself almost every day, but I’ve had a big ally, who is more powerful and more persuasive than I am, and that’s Mother Nature. The extreme climate-related weather events that have become so much more intense and more frequent are causing just about everybody to say, "Hold on a minute."

Just look at the floods here in Nashville in 2010.

Areas that had never flooded before were affected.

Lost their homes and business and had no insurance (to cover flooding) because they had never been flooded before. It was a once-in-a-thousand-year event. Well, since the flooding of Nashville, we have had seven once-in-a-thousand-year events in only six years, so obviously the old statistics have to be rewritten. …

Look at Houston, Texas, right now. This is the second year in a row they have had floods of Biblical proportions. It’s because of the climate disruption. We’ve always had storms, but now — on average — they’re much bigger and more frequent, so Mother Nature is having a big impact on public opinion, not only here in this country but all over the world.

Mother Nature certainly impacted the 11 House Republicans, last September, who acknowledged humans played a role in climate change.

And two more (recently) and a whole slew of Republican mayors have said, "Wait a minute, this is not a political issue."

Does that energize you?

Yes, very much so because I have felt for a very long time this really shouldn’t have anything to do with politics. If your house is on fire you don’t ask the firefighters whether they’re Republicans or Democrats. It’s comparable to that because we’re all in this together.

How important are the next 10 years?

They’re crucial. … I’ll say further, the next four years are crucial and here’s why: Under the Paris agreement, there is a mandatory five-year review by all the countries that signed the agreement. In 2020 we have a big chance for that review to dramatically prove the reductions that countries have agreed to make around the world.

That process will begin in 2018, so what happens in the next two, three, four years will be crucial in getting the world on the right path.

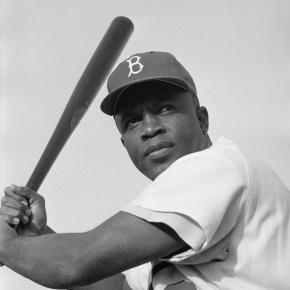

Jackie Robinson on Major League Baseball team

In 1947, Jackie Robinson was the first black man to play in Major League Baseball (MLB), and at a time when African-Americans were consigned to playing in the lower-tiered “Negro leagues.” The Brooklyn Dodgers hired the gifted Robinson and placed him on first base, assigned him the number ’42,’ and essentially ended 60 years of segregation in professional baseball. During his honorific baseball career, Robinson earned MLB’s Rookie of the Year Award, made the All-Star team for six consecutive years, and was awarded the prestigious MLB’s Most Valuable Player Award.Al Gore is only the messenger

Gore said it was traditional for people who didn’t like the message to take it out on the messenger, as baseball fans did with Robinson. Gore noted “opponents of [baseball] integration had a personal animus for Jackie Robinson,” just as he believes skeptics of catastrophic climate change have an open hostility toward him. Gore then compared global warming to the civil rights movement, rather than a scientific debate, and said that his enemies attack him because he is the most effective spokesperson for the planet.But fear not, Gore understands that this is part and parcel of being Earth’s number one diplomat. Like Robinson, who was considered a civil rights pioneer during one of America’s uglier eras, Gore believes just as adamantly he is also faced with a huge undertaking: saving mankind. Admitting in the interview that his climate change rhetoric may sound a bit over-the-top, he still thinks it’s correct to describe what he does as a “mission.” Gore says that it was his privilege to have a job that requires “every ounce of energy” he could muster into changing the world, as his self-written message dictates.

Gore on Nashville, Houston Floods

Gore also blamed Nashville’s 2010 flooding event on climate change, even though subsequent studies showed it was a confluence of weather events and waterway mismanagement that created the disaster. Gore believes these are “once-in-a-thousand-year events” and are now the new normal, though statistics don’t back up these claims. He also blamed the recent flooding in Houston, Texas, on climate change, despite his pronouncement a few short years ago that Texas’ statewide drought was caused by global warming.Gore said there is only one person with a more persuasive message than himself: Mother Nature. But he believes she’s on his side, and is his most powerful ally.

===============================

However, it wasn’t until he gave his presentation on the deck of a houseboat on Center Hill Lake that he realized the impact it might have on the public at large.

Even then, the 45th vice president of the United States never imagined the “fancy version” of his three-carousel slideshow would be developed into an Oscar-winning documentary film, "An Inconvenient Truth," or that a No. 1 bestselling book of the same name, which was released May 26, 2006, would lead to his winning the Nobel Peace Prize a year later.

With his dog, Bojangles, at his side, Gore, 68, a former reporter for The Tennessean, spoke with his hometown newspaper about the environment and climate changes on the 10th anniversary of "An Inconvenient Truth."

It really doesn’t. When I look at all the progress over the last 10 years, it sometimes makes me feel that it’s been longer than that, but emotionally, it feels like it was just a short time ago.

How good do you feel about the past 10 years?

Well, we’re far from where we need to be, so there is certainly no room for celebration, but I feel a sense of joy that we’ve made a lot more progress than many thought was possible.

The overwhelming majority of Americans in both parties and independents now agree that the climate crisis is real, man-made and must be dealt with, so that’s a lot of progress, and worldwide, every country in the world — just about — signed onto the Paris agreement and business of progress has been even more impressive in many ways than what’s happened in the policy world.

In the first three months of this year, 99 percent of all of the new electricity generation was solar and wind. Virtually no new gas or coal. Worldwide, last year, if you look at all of the new electricity generation built, 90 percent of it was solar and wind and renewables. The rapid reduction of the cost of electricity from solar photovoltaics and wind energy have astonished people all over the world. In many areas, it is now much cheaper to make electricity from sun and wind than it is from coal or gas, and that’s driving a dramatic change in business and in industry.

Nevertheless, we’re still putting 110 million tons of global warming pollution into the atmosphere every day. And it’s adding up. The cumulative amount of heat energy trapped by all the man-made pollution up there is now equal to 400,000 Hiroshima-class (atomic) bombs going off every day.

That’s disrupting weather patterns, putting a lot more water vapor into the air and causing record downpours — like the ones going on in Texas (recently) and in France and Germany and other places. And, simultaneously, it’s causing these droughts because it’s pulling the soil moisture out of the land, so with the ice melting and sea levels rising — as the scientists predicted — tropical diseases like Zika are coming into areas like the U.S.

The public’s concern has now reached the levels that the politicians almost have to do something about it.

I had a wonderful experience when I was younger in getting to know a lot of the leading climate scientists and, over the years, they have been good friends and patient enough to explain things in simple terms to me over and over again until I could get into language that was understandable to me, which I could then use to communicate what they were saying to a general audience.

I always go back to the scientists and say, "OK, here’s how I’m going to put this. Is this accurate?" And inevitably they’ll say, "You need to tweak it here and you need to tweak it there." I give them the credit for whatever I’ve been able to get across to the general audience with the movie 10 years ago and the books I’ve written then and since.

The first slideshow that I gave was back in the late ’80s and I had been giving speeches and presentations — before I built a slideshow — with flip-up charts and graphs. But I found a great guy at the National Geographic Institution, who gave me access to their picture file and helped me find some people who could help me build some graphics.

And that was believed to be high-tech.

I thought that was the cat’s meow (laughs). Then, about 10 or 12 years after that, I switched over to an Apple Macintosh and learned how to operate their program called Keynote, and when the slides got digitized, they were a whole lot easier to deal with.

You no longer had to worry about the slides being backward.

I remember one time, down at MTSU, I was showing one of the carousel versions and two or three of them upside down and backwards and it was very embarrassing because you have to stop and it’s just an ordeal.

But, anyway, when I finally got it on the computer, I was able to update it more quickly, refine it more quickly, put new images in more quickly, and this was a time when the climate science was moving very quickly.

The first time I really had the feeling that I was really going to be able to make a difference with that slideshow — long before the movie — was one Saturday night on the front end of a houseboat on Center Hill Lake where a whole gang of my rowdy friends from Smith and DeKalb and White (counties) were up there, and we were drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon and one thing led to another and I gave my slideshow on the deck of that houseboat.

I knew the gang well enough to know their reactions were not to make me feel nice about it. They really were impacted by it. I won’t quote the comments because it’s a family newspaper, but that’s the way we talk sometimes.

After that, I thought, I need to start taking this out more to a broader audience, so I started giving the slideshow a lot more frequently to basically anybody who would sit still for it, and that’s when some people in the movie industry saw it and wanted a meeting with me to say it ought to be made into a movie. I actually thought that was not a good idea.

And Davis (Guggenheim), who directed it, didn’t initially think it was a good idea.

Yeah. I’m glad he didn’t tell me that then because he was part of the gang trying to convince me to do it, but they finally got through my thick head that they knew more about making movies than I could ever imagine and that there was a way to make it into a movie. That’s how that all came about.

I don’t want to compare you to Jackie Robinson, but I’m going to draw a parallel. When you’re first at something or, in your case, out front, it’s often difficult. You had naysayers. Even though you were at the top of the New York Times bestseller list, there were people who made fun of it.

Oh, yeah. A few still do.

How do you deal with that? How are you able to keep putting yourself out there? How do you emotionally tell yourself, "It’s worth it?"

There is a time-honored tradition of people who strongly disagree with a message and take it out on the messenger, and opponents of integration had a personal animus for Jackie Robinson. Opponents of all the great social movements would take out after the advocates that were most effective in asking people to change.

As a result, I don’t take it personally when the criticism comes at me. I believe so passionately in this mission, if you will. The word "mission" might sound a little grandiose, but that’s kind of what it feels like to me. Honestly, it is a joy and a privilege to have work that justifies pouring every ounce of energy you can pour into it. That is a blessing that is to be cherished.

That’s a question that I ask myself almost every day, but I’ve had a big ally, who is more powerful and more persuasive than I am, and that’s Mother Nature. The extreme climate-related weather events that have become so much more intense and more frequent are causing just about everybody to say, "Hold on a minute."

Areas that had never flooded before were affected.

Lost their homes and business and had no insurance (to cover flooding) because they had never been flooded before. It was a once-in-a-thousand-year event. Well, since the flooding of Nashville, we have had seven once-in-a-thousand-year events in only six years, so obviously the old statistics have to be rewritten. …

Look at Houston, Texas, right now. This is the second year in a row they have had floods of Biblical proportions. It’s because of the climate disruption. We’ve always had storms, but now — on average — they’re much bigger and more frequent, so Mother Nature is having a big impact on public opinion, not only here in this country but all over the world.

Mother Nature certainly impacted the 11 House Republicans, last September, who acknowledged humans played a role in climate change.

And two more (recently) and a whole slew of Republican mayors have said, "Wait a minute, this is not a political issue."

Does that energize you?

Yes, very much so because I have felt for a very long time this really shouldn’t have anything to do with politics. If your house is on fire you don’t ask the firefighters whether they’re Republicans or Democrats. It’s comparable to that because we’re all in this together.

How important are the next 10 years?

They’re crucial. … I’ll say further, the next four years are crucial and here’s why: Under the Paris agreement, there is a mandatory five-year review by all the countries that signed the agreement. In 2020 we have a big chance for that review to dramatically prove the reductions that countries have agreed to make around the world.

That process will begin in 2018, so what happens in the next two, three, four years will be crucial in getting the world on the right path.

No comments:

Post a Comment