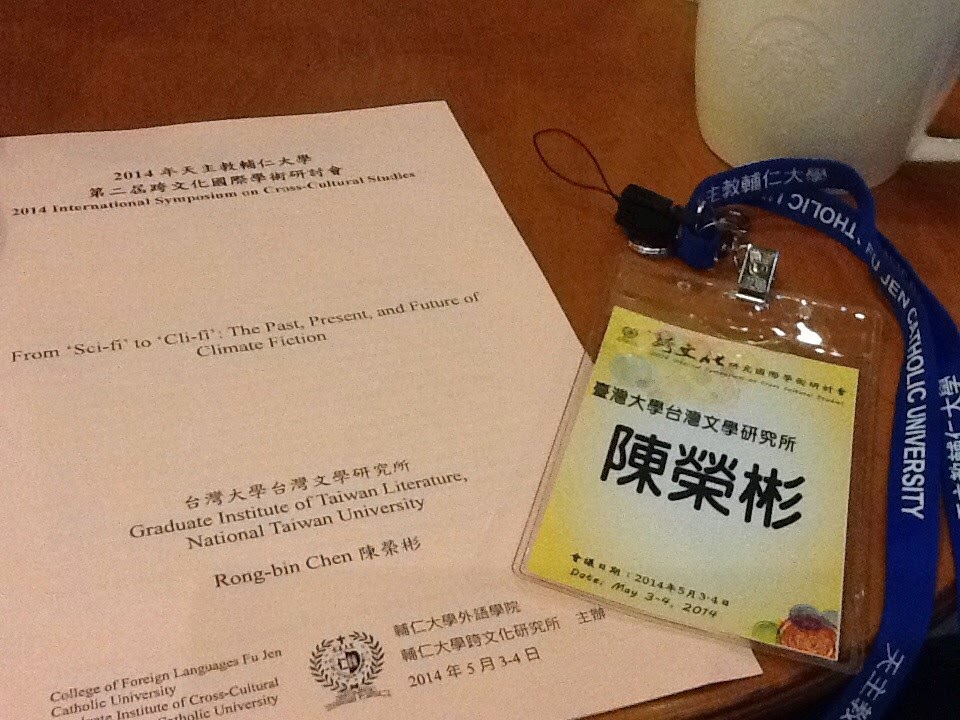

Professor Richard Chen (陳榮彬) presented this academic paper in English on ''CLI FI'' at an international conference in Taipei on May 4, 2014

From Sci-fi to “Cli-fi”:

The Past, Present, and Future of

Climate Fiction

Presented by Richard Rong-bin Chen (陳榮彬)

National Taiwan University (NTU) - Taipei

Adjunct Assistant Professor, Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature, National Taiwan University

Ever since the birth of the term “cli-fi”

on the internet, it has been a much debated sub-genre of sci-fi. One of the

controversies surround it is that whether “cli-fi,” a term coined by the

American freelance journalist Dan Bloom in 2008, is redundant when we already

have sci-fi, which is supposed to deal with the relationship between science

and fiction as a literary genre. As a preliminary academic study on “cli-fi,”

this essay tries to perform a three-fold task. First, it will try to review the

not-so-faraway history of cli-fi, whose origin might be traced back to The Drowned World (1962), the second

novel by J.G. Ballard, the renowned British sci-fi writer. Second, the essay

aims at demarcating the line between cli-fi and traditional works of sci-fi:

that is, while the former is usually filled with apocalyptic and moral

implications of climate catastrophes, the latter with the intention of

exploring the possibilities of science and its relationship with mankind.

Climate fiction is not only about global warming, but also a “global warning”

which can send messages to as many people as possible. Third, the essay argues

that the present situation of cli-fi shows the fact it has gone beyond the

reach of genre fiction, and touched upon the more serious and philosophical

issues such as the problem of “posthumanity.” With the participation of writers

such as Ian McEwan and Margaret Atwood in the discussion of cli-fi, the future

of this genre surely has abundant possibilities and more writers will be

attracted to write and more readers attracted to read works of cli-fi.

Keywords:

Science Fiction, Climate Fiction, Cli-Fi, Climate Change, Climate Catastrophes,

Posthumanity

*Adjunct Assistant Professor,

Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature, National Taiwan University

Introduction

When I first started to write this essay in

May of 2013, the Moore tornado had just struck Oklahoma, killing at

least 24 people and injuring 377 others. The catastrophic large-scale tornado

had a film-like nature which easily evoked people of scenes in bestselling

movies such as the disaster drama and sci-fi movie Twister (1996), which coincidentally set in Oklahoma. I think the

growing frequency of this type of climatic disasters is obviously one of the

reasons why the so-called “cli-fi” novels have in recent times caught much more

attention from both readers and critics alike than in the past.

Ever since the advent

of the term “cli-fi” on the Internet, it has been a much debated sub-genre of

sci-fi. One of the controversies surrounding it is that whether “cli-fi,” a

term coined by the American freelance journalist Dan Bloom in 2008, is redundant

when we already have sci-fi, which is supposed to deal with the relationship

between science and fiction as a literary genre. As a preliminary academic

study on “cli-fi,” this essay will begin with a review of the not-so-faraway

history of cli-fi, whose origin might be traced back to The Drown World (1962), the second novel by J.G. Ballard

(1930-2009), the renowned British sci-fi writer.

In the latter parts of

this essay, two more issues will be brought forth to be discussed in a more

detailed fashion. First, how should “cli-fi” be studied in the academic world

in the future? Actually this question essentially is dealing with the

relationship between “cli-fi” and “sci-fi,” and it is also about whether we

should continue to view the former as a newer part of the latter. Furthermore,

what are some of the socio-political and even philosophical messages implied in

some of the representative works of cli-fi in the recent years? What stances on

the problem of “climate change” do the writers take by writing the works?

The

Rising of “Cli-fi”: From the Past to Present

The relationship between climate (and climate

change) and literature can be as old as the Bible, which provides us with the

famous “Noah’s Ark” story depicting how a family survived an eschatological

flood. Almost 20 years ago, this specific literary relationship has been dealt

with in Climate and Literature:

Reflection of Environment (1995), a Texas Tech University Press comparative

literature academic anthology edited by Janet Pérez, which in majority focuses

on literary works of fiction from Central and Southern America.

In spring of 2003, Granta, a renowned London-based British literary

quarterly established in 1889, published a special issue entitled This Overheating World which obviously

deals with the “global warming” problem which concerns many people around the

world from a literary perspective. Both This

Overheating World and Climate and

Literature can be seen as a part of the “pre-history” of cli-fi, since the

coinage of this literary term would not be possible until 2008.

Dan Bloom, a

Taiwan-based freelance journalist and writer from Boston, was involved in

publicizing Polar City Red (2007), a

cli-fi novel written by Jim Laughter which is set in Alaska in 2075,

when he came up with the “cli-fi,” a term which obvious is the combination of “climate

change” and “fiction” and easily evokes readers of “sci-fi,” which, in turn, is

the combination of “science” and “fiction.”

The term “cli-fi” had existed

without due public attention until a series of articles were published in 2013

and heated up its popularity among both readers and critics.[1]

For example, Rodge Glass, a British novelist and university

lecturer, contributed an article entitle “Global Warning: The Rise of ‘Cli-fi’”

for The Guardian, one of the

mainstream British newspapers, writing in a welcoming tone that whenever a

literary term “gains traction it is a chance to examine not only what it says

about the writers who explore the new ground but also the readers who buy it,

read it, discuss it” (Glass). Actually, before this piece got published, we

also saw Husna Haq, a female correspondent of The Christian Science Monitor, wrote a coverage article entitled “Climate

Change Inspires a New Literary Genre: Cli-fi” in April 2013.

When talking about the rising of “cli-fi” in the literary world, three

more points are worth emphasizing. First should be the publication of

collections of “cli-fi” stories. Three years after the term had been created,

Gordon Van Gelder, a famous American science fiction magazine editor, collected

and edited more than a dozen stories for an anthology entitled Welcome to the Greenhouse: New Science

Fiction on Climate Change (2011). As Van Gelder writes in the introduction

of the book, he asked contributors to provide their perspectives on the problem

of climate change, and the answers revealed in the stories are both pessimistic

and optimistic, and most of the stories posed further problems rather than just

giving answers. In the same year, a similar effort was made by Verso, one of

the mainstream British publication houses: writer Toby Litt edited for the

company I’m With the Bears: Short Stories

From a Damaged Planet (2011), a story collection with environmentalist

stories written by award-winning novelists such as Margaret Atwood, David

Mitchell, and T. C. Boyle.

In the same manner, Tony Bradman, a senior British children’s book

writer, was responsible for the publication of Under the Weather: Stories about Climate Change (2012), a volume,

as Bradman explains in the introduction, consists of stories set in a wide

range of localities from Siberia and Canada to Australia, UK, Sri Lanka and the

Philippines. Another British project came up the next year with the

environmentalist novelist Gregory Norminton editing the story collection Beacons: Stories for Our Not So Distant

Future (2013), whose contributing novelists donated all their royalties to Stop

Climate Chaos Coalition, the UK’s largest group of people dedicated to action

on climate change and limiting its impact on the world’s poorest people.

The second place where we can see the booming of “cli-fi” is the

universities providing “cli-fi” courses. For example, in the U.K. in June 2014,

Institute of Continuing Education, Oxford University will provide a 5-day

Literature Summer School course named Cli-fi?

Climate Change and Contemporary Fiction, with lecturer Jenny Bavidge as its

course director.[2]

In winter 2014, a more formal course will be provided in Department of English,

the University of Oregon in Eugene by Professor Stephanie LeMenager. Her

course, The Cultures of Climate Change,

will be one of the graduate seminars provided by the department, which, besides

discussing interdisciplinary academic works, focuses on works of cli-fi by Nathaniel

Rich.

When the “cli-fi” articles appeared in newspapers like The Guardian and The Christian Science Monitor in April and May, 2013, many debut

writers, either coincidentally or uncoincidentally, published their first

novels, which are unanimously about climatic catastrophes. For example, in Riders of the Wind (2013) by Lee Penny,

we can see Tokyo almost destroyed by hurricanes, and in Summer Reign (2013) by G. Thomas Hedlund and Water’s Edge (2013) by Rachel Meehan, we can see the world plagued

by abnormal and extreme climatic conditions such as floods, heat waves, storms,

and draughts. This also shows a growing interest among the new-generation

writers in writing works of “cli-fi.”

“Cli-fi” and Its Implications

As a preliminary study

on “cli-fi,” one of the things to be done in this essay is an attempt to

demarcate the line between cli-fi and traditional works of sci-fi. According to

one of the exemplary definitions of science fiction provided by The Harper Handbook to Literature, it is

a genre of fiction “in which new and futuristic scientific developments propel

the plot” (418). While the definition is simple enough, it states something

obviously clear: the point of science fiction is always about exploring the

possibilities of scientific developments and its relationship with mankind.

Works of “cli-fi” can be very different from

sci-fi in this aspect. Although readers might be exposed to many meteorological

and scientific details in cli-fi stories and novels, what strike them as more

impressive and astonishing are usually the apocalyptic and moral implications

of climate catastrophes. For example, in The

Rapture (2009), a thriller written by British novelist Liz Jensen, we can

see a world plagued by the problem of melting temperatures and tornadoes,

hurricanes, and earthquakes destroyed cities like Rio de Janeiro and Istanbul.

While these plot elements might sound surreal in the past, their verisimilitude

has been greatly enhanced by Hurricane Katrina, the deadly Atlantic tropical

cyclone which almost wiped out the American city of New Orleans in 2005.

Fictional natural disasters seem real enough in this post-Katrina era of

climate change.

Another work of cli-fi

Odds against Tomorrow (2013) can be

read as a novel with a thrilling sense of reality. Not very long after the

Katrina disaster, its author Nathaniel Rich moved to New Orleans and started to

write Odds against Tomorrow, a novel

set in Rich’s hometown New York City and written about a great flood which

almost devours the whole city. Weird enough, just before the publication of the

novel, Hurricane Sandy hit the city, causing a power plant explosion and great

flood in Manhattan. In the end, it cost the city 148 lives and more than 68

billion dollars. For the New Yorkers, the illustration on the book cover cannot

be more painfully evocative: famous skyscrapers such as the Empire Building

were drowned in a water world. Actually, this motif of a world drowned in flood

dates back to more than 40 years before the advent of the term “cli-fi.” According

to many critics, the first “cli-fi” novel ever written should be The Drowned World (1962) by J. G.

Ballard, one of the masters of British contemporary science fiction writer,

which depicts a world almost drown in water after the melting of polar ice-caps

caused by solar radiation.

To borrow the phrase

used by Rodge Glass in his aforementioned The

Guardian article, climate fiction is not only about global warming, but

also a “global warning” which can send messages to as many people as possible.

Also, just like Gregory Norminton argues in the introduction of Beacons: Stories for

Our Not So Distant Future,

the story collection he edited: “Global warming is a predicament, not a story.

Narrative only comes in our response to that predicament.” In other words, for

Norminton, writing “cli-fi” carries an extra responsibility of obeying the “moral

imperative” of hope (viii-ix). “Cli-fi” differs greatly from sci-fi in the fact

that, while both of them focus on exploring scientific possibilities, “cli-fi”

actually is dealing with possible apocalyptic catastrophes which novelists feel

that they might and should help to reveal to the whole world in order to

prevent from happening. “Cli-fi” stories can do what scientific statistics

cannot: that is, motivating and persuading readers.

The Philosophical and Socio-political Aspects of “Cli-fi” Novels

One of the most imposing warnings that “cli-fi” novels can provide

is the problem of “post-humanity”: is mankind doomed to extinguish due to

climate change in the future? Is human nature going to change in possible

end-of-the-world scenes described in all kinds of religious and prophetic

writings? One novelist pay due attention to these problems in recent years is

obviously Margaret Atwood, the Canadian Booker Award winner who contributed one

story for the aforementioned anthology I’m

With the Bears: Short Stories From a Damaged Planet. Atwood used her “Oryx

and Crake” trilogy, which consists of Oryx

and Crake (2003), The Year of the

Flood (2009), and MaddAddam

(2013), to depict an imagined post-apocalyptic world caused by the technology

of cloning and a devastating “waterless flood.” Although the flood in The Year of the Flood is only

metaphoric, and actually it refers to a flood-like pandemic manmade plague

which almost wiped out mankind, detailed depictions of extreme climate

conditions, like higher radiation, warming sea water, droughts, and loss of

seasons, can be seen everywhere. If not a “cli-fi” novel in its most strict

sense, at least The Year of the Flood

can be seen as an environmentalist novel.

Michael Crichton’s techno-thriller novel State of Fear (2004) and Ian McEwan’s Solar (2010) deals with the negative and controversial issues about

the problem of climate change as a socio-political subject. In State of Fear, in order to promote the

threatening nature of global warming, a group of eco-terrorists and

environmental activists worked together to create a state of fear among the

general public. For the eco-terrorists, they wanted to save the earth at the

cost of a certain number of human lives sacrificed. And for the environmental

activists, they just wanted to perpetuate the funding they received due to the

social concern of global warming. What Crichton depicts in the novel is

actually the very thin line between environmental activism and a possible type

of terrorism founded on the basis of a fictitious pseudo-scientific theory of

climate change and global warming.

In McEwan’s Solar, the protagonist is the Nobel

Prize winner who stole the technology of artificial photosynthesis needed for

solar power plant from a deceased junior colleague. Toward the end of the

novel, he was just one step away from being the scientific hero who solved the

problem of global warming, but was found guilty of plagiarism. He was left with

multi-million debts after his business partner abandoned their power plant

project, and the panels of the plant vandalized by some unknown person. Though

the novels by Crichton and McEwan both look cynical and anti-environmentalist,

they can be seen as proofs of “cli-fi” as a genre with a self-reflexive nature,

which reminds us of how difficult it usually is to differentiate between what

is scientific and what is pseudo-scientific. While climate change can be

scientifically true to some extent, it will be an ideological tragedy to push

it to the extreme and leave no room for rational discussions.

The

Future of “Cli-fi”

In the 2003 spring

issue of Granta, one of the most

renowned British literary magazines, environmentalist Bill McKibben contributed

his article “Worried? Us?” for the special issue entitle This Overheating World and wrote that

Global Warming has

still to produce an Orwell or a Huxley, a Verne or a Wells, a Nineteen

Eighty-Four or a War of the Worlds, or in film any equivalent of On

the Beach or Doctor Strangelove. It may never do so. It may never do

so. It may be that because—fingers crossed—we have escaped our most recent

fear, nuclear annihilation via the Cold War, we resist being scared all over

again. (42)

This

argument seems to be wrong in at least two aspects. First, after J.G. Ballard

has been joined by masters like Atwood and McEwan to be included in the genre

of “cli-fi,” it looks highly probable that more and more classics of “cli-fi”

will be created in the future. Also, from the discussions so far in this essay,

obviously the fear McKibben mentions in the article should be either

non-existent or overcome long ago, since, from my previous analysis, “cli-fi”

has become a rising genre which is not merely a sub-genre of sci-fi.

To conclude the essay, it should be

stressed, three descriptive observations have been made above.

First, the

development of “cli-fi” so far takes the form of newspaper articles, story

collections, and just two university courses, so we hope more and more efforts

from the academic circles and publication houses can be made in the future.

Second, “cli-fi,” due to its responsibility of bringing climate change problems

to public attention, has a moral aspect of promoting an apocalyptic

world-vision which is not always present in sci-fi.

Third, the apocalyptic

vision of climate change and global warming problems is not always treated in a

de facto way: that is, at least we

can see some novelists, such as McEwan and Crichton, do not take this kind of

worldview for granted. For them, what is fictional is not only the genre, but

also the end of world the genre claims to avoid.

Works Cited

I

Primary Sources:

Atwood,

Margaret. The Year of the Flood.

London: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Ballard,

J. G. The Drowned World. New York:

Berkeley Books, 1962.

Bradman,

Tony. ed. Under the Weather: Stories about Climate Change. London: Frances Lincoln Children's Books, 2012.

Crichton,

Michael. State of Fear. New York:

HarperCollins, 2004.

Jenzen,

Liz. The Rapture. London: Bloomsbury,

2009.

Laughter,

Jim. Polar City Red. Deadly Niche

Press, 2012.

Litt,

Toby. ed. I’m With the Bears: Short Stories from a Damaged Planet. London: Verso, 2011.

McEwan,

Ian. Solar. New York: Random House,

2010.

Norminton,

Gregory. ed. Beacons: Stories for Our Not So Distant Future. London: Oneworld Publications, 2013.

Rich,

Nathaniel. Odds against Tomorrow. New

York: Picador, 2013.

Van

Gelder, Gordon. ed. Welcome to the Greenhouse: New Science Fiction on Climate Change. New York: OR Books, 2011.

II

Secondary Sources:

“Science Fiction.” The Harper

Handbook to Literature. Ed. Northrop Frye et al. New York: Harper, 1985. 418-9.

Glass,

Rodge. “Global Warning: The Rise of ‘Cli-fi’.” The Guardian 31 May 2013. 7 April 2014. <http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/31/global-warning-rise-cli-fi>

Haq,

Husna. “Climate Change Inspires a New Literary

Genre: Cli-fi.”

The Christian Science

Monitor

26 April 2013. 7 April 2014. <http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/chapter-and-verse/2013/0426/Climate-change-inspires-a-new-literary-genre-cli-fi>

McKibben,

Bill. “Worried?

Us?”

Ideas, Insights and

Arguments: A Non-fiction Collection. Ed. Michael

Marland. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2012. 38-44.

Norminton,

Gregory. Introduction. Beacons: Stories for Our Not So Distant Future. Ed.

Gregory Norminton. London: Oneworld Publications,

2013. vii-ix.

Pérez,

Janet and Wendell M. Aycock, ed. Climate and

Literature: Reflection of Environment. Lubbock: Texas

Tech UP, 1995.

[1] Dan Bloom contributed

an article entitled “Cli-fi Ebook to Launch on Earth Day in April” for TeleRead

(http://www.teleread.com/), the website of North American Publishing Company

(NAPCO). This might be one of the first places where the term was known to the

world.

[2] More details about

the course can be found on the institute’s website:

http://www.ice.cam.ac.uk/component/courses/?view=course&cid=11662.

No comments:

Post a Comment