REPOSTEED from original blog in UK:

REPOSTEED from original blog in UK:DJ Cockburn is writer currently based in London, after having spent most of the last 20 years meandering around the world teaching or doing science of one sort or another.

He woke up one morning and found he had 12 published stories, hence his site. The stories are listed here, with four of them available for free.

His Facebook page is here.

This post is reposted here with the permission of Mr Cockburn and may be seen in full at his site:

https://cockburndj.wordpress.com/2015/11/11/greater-minds-margaret-atwood-predicts-the-everything-change/comment-page-1/#comment-472

Greater Minds: Margaret Atwood predicts the 'Everything Change'

- Margaret Atwood was interviewed for the Center for the Science and Imagination.

- The author of the Maddaddam trilogy speculates on climate change and the future.

- The dispute about whether what she writes is science fiction or not persists.

- She regards the term ‘climate change’ as limiting, preferring ‘everything change’.

So said Margaret Atwood during a speech about cli-fi and other genres to Ed Finn, director of Arizona State University’s Center for the Science and Imagination. It was part of an interview that is reproduced in full in Slate, though some of her shinier pearls of wisdom were assembled into a video montage:

Atwood has pulled off the rare trick of being a luminary in both the literary and science fiction fields. Her first novel, The Edible Woman (1969), told the story of a middle class Canadian woman’s dysfunctions and machinations, a theme she returned to in many subsequent novels such as Cat’s Eye (1988) and The Robber Bride (1993). In The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), she projected the theme into the future state of Gilead, in which women are chattels of men. She merged the genres in the Booker Prize winning The Blind Assassin (2000), which used science fiction short stories both as a homage to 1940s pulp writers and as an allegory for a story of one of them.

The Handmaid’s Tale is often cited as a seminal work of feminist science fiction, though she’s always preferred the term ‘speculative fiction’. She moved even further into the realms of science fiction with the Maddaddam trilogy of Oryx and Crake (2003), Year of the Flood (2009) and Maddaddam (2013), which combine a dystopian and a post-apocalyptic future. She gave us a frighteningly plausible vision of the near future in which climate change and wealth inequalities divide Americans between gated communities and slums until a genetic engineer decided enough is enough and unleashes the ‘flood’ in the form of a particularly virulent plague.

When is science fiction not science fiction?

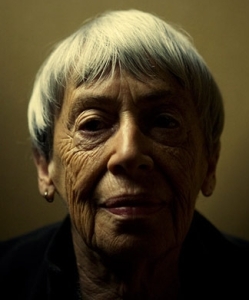

Many readers, who allowed their idea of science fiction to be defined by Hollywood, still look perplexed by the suggestion that The Handmaid’s Tale and the Maddaddam trilogy are in fact science fiction. Atwood herself prefers the term ‘speculative fiction’, a distinction that Ursula K Le Guin rather mischievously objected to in an otherwise very favourable review of Year of the Flood. Gentle as Le Guin’s words were, she was clearly accusing Atwood of being disingenuous:

She says that everything that happens in her novels is possible and may even have already happened, so they can’t be science fiction, which is “fiction in which things happen that are not possible today”. This arbitrarily restrictive definition seems designed to protect her novels from being relegated to a genre still shunned by hidebound readers, reviewers and prize-awarders. She doesn’t want the literary bigots to shove her into the literary ghetto. Who can blame her?

Those of us who enjoy science fiction have no difficulty in recognising the ‘literary bigots’ Le Guin refers to. Le Guin has been an unashamed leader in the realms of science fiction and fantasy for years, and often speaks out against the perception that her chosen genres are inferior literature. She presumably wanted Atwood to strike a blow for the genres by informing the ‘literary bigots’ who admire The Handmaid’s Tale that they are in fact admiring science fiction.

Wondertales

In a 2011 interview with Mariella Frostrup on BBC Radio 4’s Open Book, Atwood described her subsequent conversation with Le Guin:

We both agreed that there are books under the great subheading of wondertales. There are books that described things that really could happen and there are other books that describe things that really could not happen so the books that I’ve written, Oryx and Crake, The Handmaid’s Tale and Year of the Flood; they don’t go outside the bounds of imminent possibility. It’s not planet X, it’s this earth, it’s not people from Mars, it’s us.

The interview can be downloaded here, and takes place in the first eight minutes of the programme.

As Finn would find out in his interview, Frostrup was finding that a direct question rarely elicits a direct answer from Atwood. Instead, she gives her views and leaves it to the rest of us to decide whether it meant ‘yes’, ‘no’, or more likely, ‘yes and no’.

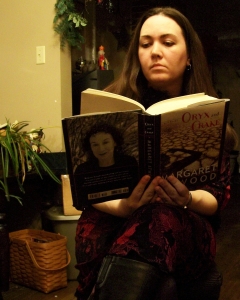

Promotional photograph for BBC audio dramatization of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ (Kelly Garbato [CC / Flickr])

A tale for another century

Whether or not Atwood’s novels are science fiction, she makes no secret of her interest in the future. Last year she became the first author to contribute a story to the Future Library Project, to which one author will be asked to contribute every year for a hundred years. The stories will be kept in boxes and, assuming the project is sustained for its full duration, the 100 boxes will be opened in 2114.

Simply participating in a century-long project at its inception shows her interest in being a part of the future, and perhaps more optimism than she demonstrated in the interview with Slate. When asked what she would most like to know about the future, she wanted to ask, ‘will there be people in a hundred years?’.

Perhaps she just wants to know if anyone will ever read the story she put in the Future Library.

''Cli-fi'' pioneer

Oryx and Crake wasn’t the first exploration of climate change in fiction, but the Maddaddam trilogy is among the best known. ''Climate fiction'' now has its own Wikipedia page and has been given the abbreviation ‘cli-fi’, which are indications as strong as any that the genre is gaining recognition.

Atwood’s reference to climate change as ‘everything change’, quoted at the beginning of this article, may well become a defining statement of the subgenre. Climate change will have knock-on effects that will be complex and probably unpredictable. A recent example would be the failure of rainfall in Turkey’s Taurus Mountains which led to the failure of agriculture in Syria, which in turn led to mass internal migration and civil war, which led to the current refugee crisis in Europe, a subject I pontificated about a few weeks ago. Rainfall patterns in Turkey led directly, if proximately, to demonstrations in Germany on an issue that many of the demonstrators didn’t even realise was related.

Hope in the toolkit

Atwood went on to say, ‘it’s rather useless to write a gripping narrative with nothing in it but climate change because novels are always about people’. The Maddaddam trilogy is very much about people, but their lives are defined by the climate changing around them.

Atwood’s science fiction (or speculative fiction, or ''cli-fi'' or however she would like to categorise it) tends toward the dystopian and apocalyptic, and several of Finn’s questions look like attempts to establish whether she is as pessimistic as her novels. The nearest he got was an answer was when he asked directly, ‘are you hopeful about the future?’

She replied:

I think hope is among a number of things that are part of the human toolkit. It’s built in unless people are suffering from clinical depression. You might even define that state as something’s gone wrong with the hope. We are all hopeful in that respect. What was it that Oscar Wilde said about second marriages—a triumph of hope over experience. He was so naughty.

So does quoting an acerbic comment by Oscar Wilde mean that she is or is not hopeful? Characteristically, she leaves it to us to judge. What do you think? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

No comments:

Post a Comment