When Did the End of HUMANKIND Begin?

A scientific debate that’s oddly amusing to entertain: At what point, exactly, did mankind irrevocably put the Earth on the road to ruin?

Theory 1: Was it when we began to blow ourselves up?

*This article by Robert Sullivan appeared in the June 15, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

By Sunday, the notion of preparing for a discussion was causing me a kind of dread, in part owing to my dread-inclined nature, in part to the reading list: everything from “Art for the Anthropocene Era,” in Art in America last winter, to “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene,” in New Literary History, which begins with a kind of hands-in-the-air-and-surrender sentiment: “How can we absorb the odd novelty of the headline: ‘The amount of CO2 in the air is the highest it has been for more than 2.5 million years — the threshold of 400 ppm of CO2, the main agent of global warming, is going to be crossed this year’?” How can we indeed? Elizabeth Kolbert’s work on extinctions was on the list, as was Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature, a book I read in 1989, at which point I distinctly remember predicting it would change everyone’s thinking on global warming, which it did and, terrifyingly, didn’t at all. And now the Anthropocene was everywhere, like a marketing campaign, or taxes. “I have a term that I’ve been throwing out occasionally,” Erle Ellis, a global ecologist at the University of Maryland, told me. “It’s the Zeitangst.”

I went to my friend’s salon — a social scientist presented some interesting research about changing human behavior, followed by likewise interesting dialogue and great cake — and I left determined to better understand the definition of the Anthropocene, only in so doing I found myself nearly lost, swallowed up in the tar pit of debate.

The Anthropocene does not, in the strictest sense, exist. By the standards of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the administrators of the geologic time scale — that old-school conceptual ruler notched with eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages stretching back to what we refer to as the Earth’s beginning, about four and a half billion years ago — we are living in the epoch called the Holocene. The proposition, however, is that this is no longer true — that we are now in a new epoch, one defined by humanity’s significant impact on the Earth’s ecosystems.

This has come, for obvious reasons, to be freighted with political portent. Academics, particularly scientific ones, are excited by this notion. But they are not satisfied with the term as a metaphor; they seek the authority of geologists, the scientists historically interested in marking vast tracts of time, humanity’s official timekeepers. And so, to learn more, I Skyped with Jan Zalasiewicz, a delightful paleogeologist at the University of Leicester and the chair of the International Commission on Stratigraphy’s Anthropocene Working Group. “Nottingham Castle is built on Sherwood sandstone,” he noted, listing the local geologic sites, “which has cut into it Britain’s oldest pub, from the time of the Crusades. If you ever visit Nottingham, you must have a pint!”

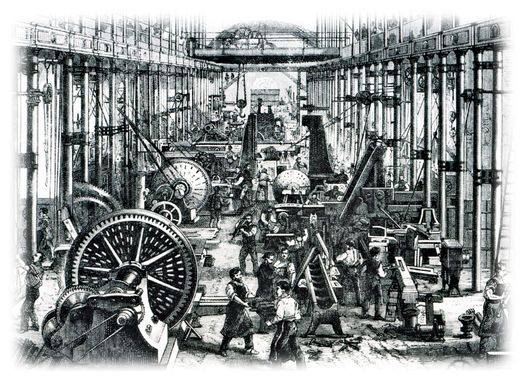

I asked Zalasiewicz when he’d first heard of the Anthropocene. He cited a 2002 paper in Nature written by Paul Crutzen, a Nobel Prize–winning chemist and a prominent practitioner of Earth-system science, which is the study of the interactions between the atmosphere and other spheres (bio-, litho-, etc). “I read it and I thought, How interesting. What a nice idea. And then, like a lot of geologists, I forgot about it — until the word began to appear in the literature, as if it was formal, without irony, without inverted commas.” In Nature, Crutzen urged the scientific community to formally adopt what he named the Anthropocene (anthro from the Greek anthrópos, meaning “human being”) and to mark its beginning at the start of the Industrial Revolution. The evidence he cited is too depressing to recount in full here: The human population has increased tenfold in the past 300 years; species are dying; most freshwater is being sucked up by humans; not to mention the man-induced changes in the chemical composition of the atmosphere — essentially, all the facts the world is ignoring, avoiding, or paying people to obfuscate.

Crutzen’s proposal barely registered in Zalasiewicz’s field. “It was a geologic concept launched by an atmospheric chemist within an Earth-science-systems context,” he explained. (Translation: An NHL player suggested an NBA rule.) But by the time it came up at the Geological Society of London in 2008, the ICS was in the strange position of debating a term that had already been accepted not just by laypeople but by other scientists — especially the Earth-system scientists who first trumpeted global warming. Anthropocene has proved wildly appealing. For laypeople, it’s big and futuristic and implies a science-induced bad ending; for climate-change scientists, it marks all their hard work in the lucidly solid and enduring traditions of geology. Everybody likes that it is a simple, epic, ostensibly scientific stake in the Earth that says “We’re fucked.”

Academic papers, from myriad sources, have since poured in, in a situation reminiscent of the cataclysmic flood that suddenly overran the Pacific Northwest 15,000 years ago, on the day that glacial Lake Missoula’s ice dams gave way. The aim is to identify an acceptable “golden spike” — traditionally a mark, visible in the Earth, where a geologist can observe a change in the past. But to be accepted as a spike, formal criteria must be met. The marker must be geosynchronous‚ i.e., align with similar markers around the world from the same time. It must be technical and practical, something scientists in the field can find in the rocks and sediments. This golden-spike search has felt backward to many geologists, who historically have first found a change in the rocks and then named it, rather than observing a change and then scouring the rocks for a marker.

If you are pushing for an Anthropocene golden spike at 10,000 to 50,000 years ago, then you are endorsing a spike at the extinction of the megafauna, the massive creatures like saber-toothed tigers and the Coelodonta, a Eurasian woolly rhinoceros that was likely hunted away by humans. This is a spike favored by some archaeologists whose long view is geologic in itself and admirable in its clarity: Humanity’s impact, they argue, starts near the beginning of humanity. (The moment humans controlled fire is another spike candidate.) However, for many stratigraphers, these early proposals fall short. There is scant geosynchronous evidence, plus the larger question of whether hunting mammoths is really what we’re talking about when we’re talking about a man-doomed world.

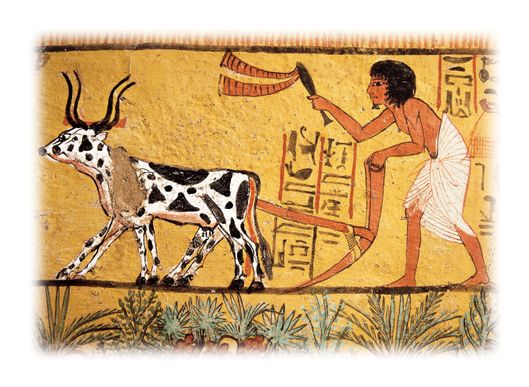

So then maybe it’s not the beginning of humanity itself but the moment man began to farm, a development that destroyed plants and thus caused other extinctions. At that same time, many forests were converted to grazing lands, often via controlled, carbon-releasing fires. Votes for a farming spike might come from anthropologists and ecologists. Still, while it might be possible to track the fossil pollen from domesticated plants, farming takes off unevenly, beginning 11,000 years ago in Southwest Asia but not until 4,000 or 5,000 years ago in Africa and North America.

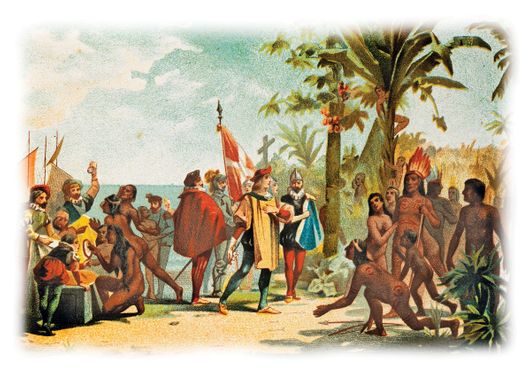

This March, two scientists from University College, London, offered a new candidate. Writing in Nature, Simon Lewis, an ecologist, and Mark Maslin, a geographer, proposed the arrival of Europeans in the Caribbean in 1492 — what the authors of the paper called “the largest human population replacement in the past 13,000 years, the first global trade networks linking Europe, China, Africa and the Americas, and the resultant mixing of previously separate biotas, known as the Columbian Exchange.” Counterintuitively, this spike correlates with a decrease in carbon in the atmosphere that began in 1610, caused by the destruction of North American agricultural civilizations (likely from disease spread by humans) and the return of carbon-sucking woodlands. Lewis and Maslin have named this dip the Orbis spike (Orbis for “world”) because, they write, after 1492, “humans on the two hemispheres were connected, trade became global, and some prominent social scientists refer to this time as the beginning of the modern ‘world-system.’ ” And yet the betting is that the Orbis spike will not make the cut among the geologists: The dip in carbon dioxide is small and observable only in remote ice, just for starters.

A lot of stratigraphers find this whole exercise useless — an attempt by well-meaning activists to hijack the language of geology and then justify their work by inventing arguably nonexistent spikes. “What’s the stratigraphic record of the Anthropocene?” asked Stan Finney, a geologist at California State University at Long Beach. “There’s nothing. Or it’s so minimal as to be inconsequential.” He is not, he insisted, saying humans have not affected the Earth. Au contraire. “I live in L.A., and I’m disgusted by the spread of the city,” he said. “And sure, humans have impacted the Earth. There’s no debate. The debate is over what we do in the ICS and what’s the nature of our units and the concept. And that’s not really a debate.” Marking the Anthropocene at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution or farming or at the sailing of the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María would be, to his mind, a ridiculous privileging of human history over rock history.

The Anthropocene Working Group is hoping to present its findings at the International Geological Congress in 2016, and that fact alone is an evolution worth spiking, a change in science’s ecology. (It took more than 50 years for the Holocene to be formalized.) Zalasiewicz told me that opinions are coalescing. “Not unanimously, but we tend to be coming round to the mid–20th century,” he said, since evidence of man-made environmental destruction is so easy to find then. In the meantime, the argument is not merely over the spikes, or even the formal adoption of a new epoch; it’s over what the arrival of the term means for science and everyone else. “There’s basically a tidal wave of change coming down,” Haff told me, “and I think it’s incumbent upon the intellectual and professional community to try to respond in some positive way.”

For geologists, this means figuring out how to bring your field up to speed without bastardizing it. For many Earth-system scientists and their sympathizers, it means using the Anthropocene to scare the crap out of the world (for a good reason, obviously, but still); they talk about our being at a tipping point, that we should work to prepare for the worst. Others find the term empowering. Last summer, Andrew C. Revkin, who runs DOT EARTH blog at the NYY and a journalist and AWG member who has scrupulously documented the Anthrocene conversation (and coined the idea ten years before Crutzen), used the phrase “‘good’ Anthrocene” to suggest that the epoch might not be all gloom. He was swiftly attacked; the ethicist Clive Hamilton called the phrase a “failure of courage, courage to face the facts,” and Elizabeth Kolbert tweeted that good and Anthrocene were “two words that probably should not be used in sequence.”

Over the last year, Stephanie Wakefield, a geographer at CUNY Queens, has been helping organize gatherings at a space in an old building in Ridgewood called Woodbine, where friends and neighbors attend lectures, neighborhood meetings, gardening events, you name it. Wakefield herself has given a few talks on the history of apocalyptic thinking in America, a topic that tends to numb people into inaction. To her, the term Anthropocene is galvanizing, like a wake that goes well: One epoch has died to be replaced by something else, and we all have a stake in what that new world will be.

“People talk for hours,” she says of the public discussions. “There’s a new vibe to it. Everyone gets to the heart of it really fast.” A few months ago, a guest speaker Skyped in from England: Jan Zalasiewicz. The people of Ridgewood had lots of questions for him. “Jan said something really interesting that I had not thought of before,” Wakefield said, “which is that we all see that the popularity of the Anthropocene allows for all these new things — for people to meet across barriers, to talk about revolutionary things outside of the political sphere. How are we going to remake life?

Let’s figure it out.” Zalasiewicz explained why he thinks it’s important for geologists to recognize the shift in some way. “It gives it that legitimacy,” Wakefield said about Zalasiewicz’s talk. “If it’s just a phrase, then it’s like, well, there are a lot of phrases.”

*This article appeared in the June 15, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment