Letters to the Future

The Paris Climate Project

By Various Authors

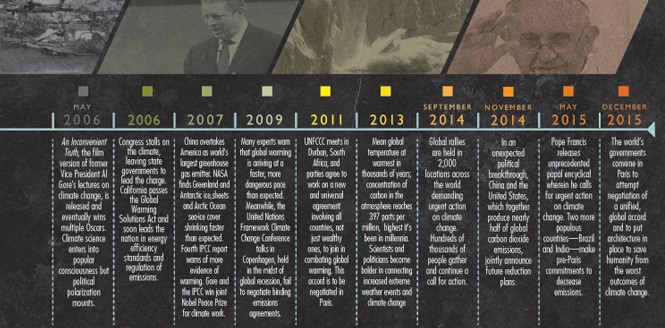

Despite the fresh tragedy of the Paris terrorist attacks, the French government remains committed to hosting the U.N. Climate Change Conference (known as COP21 or FLOP21, depending on your POV) scheduled in Paris from Nov. 30 to Dec. 11. As such, world leaders from mucho countries (President Obama and Japanese PM Shinzo Abe are slated to attend) will convene in Paris to consider passage of a binding global treaty aimed at reducing the most dangerous impacts of global warming. While some speculate that the attacks actually have improved the odds of a successful outcome, others fear that efforts to achieve a global climate pact could stall.

''Letters to the Future,'' a national project involving more than 40 alternative weeklies across the United States, set out to find authors, artists, scientists and others willing to get creative and draft letters to future generations of their own families, predicting the success or failure of the Paris talks COP21 or er FLOP21 —and what came after.

Some participants were optimistic about what is to come — some, like Dan Bloom with his ''A LETTER TO 2499'', not so much. Oy! But read it first and then weep for our descendants!

We hereby present some personalized visions of the future. To find out how locals are involved in the conference, see "Hot Topic," on p. 12. Read even more letters (and add one of your own) at LettersToTheFuture.org.

by Dan Bloom

Note to readers: This text came in the mail the other day, and I am not sure whether to publish it here as fiction or nonfiction as the author of the piece did not tell me her wishes. It reads to me like fiction, like the beginning of a cli fi novel she has planned. She didn’t tell me much about the story or her plans for it, but here is the text as she sent it to me, with just some slight edits for clarity for those readers new to the cli-fi genre.

Dear Future World, Future Humanity, if you are even there then!

I’m writing these words to you from my home in Baffin Island in 2099, when climate change and man-made global warming (AGW) were already on our radar and causing deep concerns around the world. Did COP21 make any difference? I assume not. You are living 400 years later, if you are indeed there, and you are preparing to die, to lie down and die, knowing your time in the cosmos has come, humanity’s time, the end of the human species, as climate-related and AGW-related massive human die offs threaten the very extinction of our species.

I have no advice for you since I cannot see that far ahead into the future, but I do know this: you and your fellow Earthlings will die soon via unspeakable, indescribable, untimely deaths — billions of you in a series of massive human die offs! — die to AGW impact events beyond your control. They will not be easy deaths, they will not be comfortable deaths, they will not be acceptable deaths. God bless you, although I am not sure any of you believe in God anymore there.

Sadly, inexorably, we have left you and those survivors with you in 2499 with no future and no escape hatch, and you are all going to die, all of you, en masse, soon.

Blame us, not yourselves. And as you prepare to lay down and die, not just where you are but around the world as well, in Australia, Canada, Thailand, all of Africa, all of South and Central America, all of the Lower 48 states of the uninhabitable former United State of America, know that you die as all humans before you did, over the past 5000 years, over the past 100,000 years, over the past 3,000,000 years. Numbers. Years. Past generations of the once human species. All gone now or soon to be gone completely. You, too, dear readers of this letter from the past.

I have no more words to say to you, all ye who prepare now there in 2499 A.D. — year of what God? — all you who prepare now to lay down your lives and die with great sadness and regret, and may you find your ways to die with inner peace and grace, no matter which gods or goddesses you believe in then. I cry for thee, o future generations of 2499. There is no future after you. Time will stop.

Blame us, don’t blame yourselves. Blame those who came before you in the 1800s, in the 1900s, in the early centuries of the Third Millennium. We created AGW and once we became aware of the Climatestein monster we had created, we did little to stop it. Our leaders did nothing. Greed and convenience ruled our world and we left you with, with, with this.

There were voices of concern, but they fell on deaf ears. There were public mass demonstrations and marches, but they accomplished nothing. The United Nations said it wanted to act, but it did nothing.

I only hope that you find it in your hearts to die with inner peace and inner grace, and to die in quiet, soothing ways. It’s not going to be a pretty picture, but please be strong is my message from 2099. Be physically strong, be emotionally strong, be spiritually strong.

Go gently into this dark dark night that awaits you and the rest of humankind, the very remnants of humanity. Find your way. I pray for you.

#####

MORE STORIES BELOW:

Brief OpportunitiesDear Great-Great-Granddaughter,

Do you remember your grandmother, Veronica? I am writing to you on the very day that your grandmother, Veronica, turned 7 months old—she is my first grandchild. That is how quickly time passes and people are born, grow up, and pass on. When I was your age—now 20 (Veronica was my age, 65, when you were born), I did not realize how brief our opportunities are to change the direction of the world we live in. The world you live in grew out of the world I live in, and I want to tell you a little bit about the major difficulties of my world and how they have affected your world.

On the day I am writing this letter, the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives quit his job because his party—called "the Republicans"—refused absolutely to work with or compromise with the other party—now defunct—called "the Democrats." The refusal of the Republicans to work with the Democrats was what led to the government collapse in 2025, and the breakup of what to you is the former United States. The states that refused to acknowledge climate change or, indeed, science, became the Republic of America, and the other states became West America and East America. I lived in West America. You probably live in East America, because West America became unlivable owing to climate change in 2050.

That the world was getting hotter and dryer, that weather was getting more chaotic, and that humans were getting too numerous for the ecosystem to support was evident to most Americans by the time I was 45, the age your mother is now. At first, it did seem as though all Americans were willing to do something about it, but then the oil companies (with names like Exxon and Mobil and Shell) realized that their profits were at risk, and they dug in their heels. They underwrote all sorts of government corruption in order to deny climate change and transfer as much carbon dioxide out of the ground and into the air as they could. The worse the weather and the climate became, the more they refused to budge, and Americans, but also the citizens of other countries, kept using coal, diesel fuel, and gasoline. Transportation was the hardest thing to give up, much harder than giving up the future, and so we did not give it up, and so there you are, stuck in the slender strip of East America that is overpopulated, but livable. I am sure you are a vegan, because there is no room for cattle, hogs, or chickens, which Americans used to eat.

West America was once a beautiful place—not the parched desert landscape that it is now. Our mountains were green with oaks and pines, mountain lions and coyotes and deer roamed in the shadows, and there were beautiful flowers nestled in the grass. It was sometimes hot, but often cool. Where you see abandoned, flooded cities, we saw smooth beaches and easy waves.

What is the greatest loss we have bequeathed you? I think it is the debris—the junk, the rotting bits of clothing, equipment, vehicles, buildings, etc.—that you see everywhere and must avoid. Where we went for walks, you always have to keep an eye out. We have left you a mess. But I know that it is dangerous for you to go for walks—the human body wasn't built to tolerate lows of 90 degrees F and highs of 140. When I was alive, I thought I was trying to save you, but I didn't try hard enough, or at least, I didn't try to save you as hard as my opponents tried to destroy you. I don't know why they did that. I could never figure that out.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992 for her novel A Thousand Acres, Jane Smiley has composed numerous novels and works of nonfiction.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992 for her novel A Thousand Acres, Jane Smiley has composed numerous novels and works of nonfiction.

Sorry About ThatDear Rats of the Future:

Congratulations on your bipedalism: it's always nice to be able to stand tall when you need it, no? And great on losing that tail, too (just as we lost ours). No need for that awkward (and let's face it: ugly) kind of balancing tool when you walk upright, plus it makes fitting into your blue jeans a whole lot easier. Do you wear blue jeans—or their equivalent? No need, really, I suppose, since you've no doubt retained your body hair. Well, good for you.

Sorry about the plastics. And the radiation. And the pesticides. I really regret that you won't be hearing any bird song anytime soon, either, but at least you've got that wonderful musical cawing of the crows to keep your mornings bright. And, of course, I do expect that as you've grown in stature and brainpower you've learned to deal with the feral cats, your one-time nemesis, but at best occupying a kind of ratty niche in your era of ascendancy. As for the big cats—the really scary ones, tiger, lion, leopard, jaguar—they must be as remote to you as the mammoths were to us. It goes without saying that with the extinction of the bears (polar bears: they were a pretty silly development anyway, and of no use to anybody beyond maybe trophy hunters) and any other large carnivores, there's nothing much left to threaten you as you feed and breed and find your place as the dominant mammals on earth. (I do expect that the hyenas would have been something of a nasty holdout, but as you developed weapons, I'm sure you would have dispatched them eventually).

Apologies, too, about the oceans, and I know this must have been particularly hard on you since you've always been a seafaring race, but since you're primarily vegetarian, I don't imagine that the extinction of fish would have much affected you. And if, out of some nostalgia for the sea that can't be fully satisfied by whatever hardtack may have survived us, try jellyfish. They'll be about the only thing out there now, but I'm told they can be quite palatable, if not exactly mouth-watering, when prepared with sage and onions. Do you have sage and onions? But forgive me: of course you do. You're an agrarian tribe at heart, though in our day, we certainly did introduce you to city life, didn't we? Bright lights, big city, right? At least you don't have to worry about abattoirs, piggeries, feed lots, bovine intestinal gases and the like—or, for that matter, the ozone layer, which would have been long gone by the time you started walking on two legs. Does that bother you? The UV rays, I mean? But no, you're a nocturnal tribe anyway, right?

Anyway, I just want to wish you all the best in your endeavors on this big blind rock hurtling through space. My advice? Stay out of the laboratory. Live simply. And, whatever you do, please—I beg you—don't start up a stock exchange.

With best wishes,

T.C. Boyle

P.S. In writing you this missive, I am, I suppose, being guardedly optimistic that you will have figured out how to decode this ape language I'm employing here—especially given the vast libraries we left you when the last of us breathed his last.

A novelist and short story writer, T.C. Boyle has published 14 novels and more than 100 short stories.

A novelist and short story writer, T.C. Boyle has published 14 novels and more than 100 short stories.

Seize the MomentDear Descendants,

The first thing to say is, sorry. We were the last generation to know the world before full-on climate change made it a treacherous place. That we didn't get sooner to work slowing it down is our great shame, and you live with the unavoidable consequences.

That said, I hope that we made at least some difference. There were many milestones in the fight—Rio, Kyoto, the debacle at Copenhagen. By the time the great Paris climate conference of 2015 rolled around, many of us were inclined to cynicism.

And our cynicism was well-taken. The delegates to that convention, representing governments that were still unwilling to take more than baby steps, didn't really grasp the nettle. They looked for easy, around-the-edges fixes, ones that wouldn't unduly alarm their patrons in the fossil-fuel industry.

But so many others seized the moment that Paris offered to do the truly important thing: Organize. There were meetings and marches, disruptions and disobedience. And we came out of it more committed than ever to taking on the real power that be.

The real changes flowed in the months and years past Paris, when people made sure that their institutions pulled money from oil and coal stocks, and when they literally sat down in the way of the coal trains and the oil pipelines. People did the work governments wouldn't—and as they weakened the fossil-fuel industry, political leaders grew ever so slowly bolder.

We learned a lot that year about where power lay: less in the words of weak treaties than in the zeitgeist we could create with our passion, our spirit and our creativity. Would that we had done it sooner!

An author, educator and environmentalist, Bill McKibben co-founded 350.org, a planet-wide grass-roots climate-change movement. He has written more than a dozen books.

An author, educator and environmentalist, Bill McKibben co-founded 350.org, a planet-wide grass-roots climate-change movement. He has written more than a dozen books.

Political BoneheadsHello? People of the future ... Anyone there?

It's your forebears checking in with you from generations ago. We were the stewards of the Earth in 2015—a dicey time for the planet, humankind, and life itself. And ... well, how'd we do? Anyone still there? Hello.

A gutsy, innovative, and tenacious environmental movement arose around the globe back then to try lifting common sense to the highest levels of industry and government. We had made great progress in developing a grass-roots consciousness about the suicidal consequences for us (as well as those of you future earthlings) if we didn't act pronto to stop the reckless industrial pollution that was causing climate change. Our message was straightforward: When you realize you've dug yourself into a hole, the very first thing to do is stop digging.

Unfortunately, our grass-roots majority was confronted by an elite alliance of narcissistic corporate greedheads and political boneheads. They were determined to deny environmental reality in order to grab more short-term wealth and power for themselves. Centuries before this, some American Indian cultures adopted a wise ethos of deciding to take a particular action only after contemplating its impact on the seventh generation of their descendants. In 2015, however, the ethos of the dominant powers was to look no further into the future than the three-month forecast of corporate profits.

As I write this letter to the future, delegations from the nations of our world are gathering to consider a global agreement on steps we can finally take to rein in the looming disaster of global warming. But at this convocation and beyond, will we have the courage for boldness, for choosing people and the planet over short-term profits for the few? The people's movement is urging the delegates in advance to remember that the opposite of courage is not cowardice, it's conformity—just going along with the flow. After all, even a dead fish can go with the flow, and if the delegates don't dare to swim against the corporate current, we're all dead.

So did we have the courage to start doing what has to be done? Hello ... anyone there?

A national radio commentator, writer and public speaker, Jim Hightower is also a New York Times best-selling author.

A national radio commentator, writer and public speaker, Jim Hightower is also a New York Times best-selling author.

Shift the Food SystemDear Future Family,

I know you will not read this note until the turn of the century, but I want to explain what things were like back in 2015, before we figured out how to roll back climate change. As a civilization, we were still locked into a zero-sum idea of our relationship with the natural world, in which we assumed that for us to get whatever we needed, whether it was food or energy or entertainment, nature had to be diminished. But that was never necessarily the case.

In our time, the U.S. Department of Agriculture still handed out subsidies to farmers for every bushel of corn or wheat or rice they could grow. This promoted a form of agriculture that was extremely productive and extremely destructive—of the climate, among other things.

Approximately one-third of the carbon then in the atmosphere had formerly been sequestered in soils in the form of organic matter, but since we began plowing and deforesting, we'd been releasing huge quantities of this carbon into the atmosphere. At that time, the food system as a whole—that includes agriculture, food processing and food transportation—contributed somewhere between 20 percent to 30 percent of the greenhouse gases produced by civilization—more than any other sector except energy. Fertilizer was always one of the biggest culprits for two reasons: It's made from fossil fuels, and when you spread it on fields and it gets wet, it turns into nitrous oxide, which is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Slowly, we convinced the policy makers to instead give subsidies to farmers for every increment of carbon they sequestered in the soil.

Over time, we began to organize our agriculture so that it could heal the planet, feed us and tackle climate change. This began with shifting our food system from its reliance on oil, which is the central fact of industrial agriculture (not just machinery, but pesticides and fertilizers are all oil-based technologies), back to a reliance on solar energy: photosynthesis.

Carbon farming was one of the most hopeful things going on at that time in climate change research. We discovered that plants secrete sugars into the soil to feed the microbes they depend on, in the process putting carbon into the soil. This process of sequestering carbon at the same time improved the fertility and water-holding capacity of the soil. We began relying on the sun—on photosynthesis—rather than on fossil fuels to feed ourselves. We learned that there are non-zero-sum ways we could feed ourselves and heal the earth. That was just one of the big changes we made toward the sustainable food system you are lucky enough to take for granted.

A teacher, author and speaker on the environment, agriculture, the food industry, society and nutrition, Michael Pollan's letter is adapted from an interview in Vice Magazine.

A teacher, author and speaker on the environment, agriculture, the food industry, society and nutrition, Michael Pollan's letter is adapted from an interview in Vice Magazine.

You Deserve a Chance

As a young boy growing up in Searchlight, the unique beauty of the Nevada desert was my home. Our family didn't travel or take vacations, but we were able to visit Fort Piute Springs which was just 15 miles from our home. Fort Piute Springs was a starkly beautiful place. From the gushing ponds of water to the beautiful lily pads and cattails, Fort Piute's beauty was magical. Decades later, I returned to visit Fort Piute Springs and found the magical place of my childhood in ruins. I remember thinking how sad it was that my descendants would never get to appreciate the stark beauty of the desert I cherished as a child. It was in that moment that I decided to fight to protect our environment.

As a young boy growing up in Searchlight, the unique beauty of the Nevada desert was my home. Our family didn't travel or take vacations, but we were able to visit Fort Piute Springs which was just 15 miles from our home. Fort Piute Springs was a starkly beautiful place. From the gushing ponds of water to the beautiful lily pads and cattails, Fort Piute's beauty was magical. Decades later, I returned to visit Fort Piute Springs and found the magical place of my childhood in ruins. I remember thinking how sad it was that my descendants would never get to appreciate the stark beauty of the desert I cherished as a child. It was in that moment that I decided to fight to protect our environment.

Throughout my career, I fought to protect my home and my country from the permanent damage of climate change. I thought about the world you would live in, the burdens you would face and the health issues that could one day challenge your very existence. You deserve a chance to experience the beautiful world that I grew up in. We all need clean air, clean water and natural resources to lead healthy lives. The idea that our actions could jeopardize your future was simply unbearable.

The only way to solve this problem was if we all worked together to save the planet for you and future generations. During my lifetime, the overwhelming majority of scientists across the world concluded that pollution from burning fossil fuels was beginning to raise temperatures and alter our climate. These scientists predicted that if countries failed to work together to replace fossil fuels with cleaner energy sources, the world would face uncontrollable rising temperatures and sea levels, water shortages, climate-fueled migration crises, and landscape-altering wildfire, drought, and extreme weather.

At the close of 2015, the world finally did something about it. Everybody knew we needed to address climate change and that a failure to lead could destroy the progress we fought so hard to achieve and endanger your future. In the face of this reality, the United States pressed on and led a historic global agreement to change the course of climate change worldwide. We had already done so many things to make Nevada a cleaner, greener place—but now the entire world was ready to join us.

I'm proud of the work we did to protect our environment for you. I hope, by now, you can run just about everything on renewable energy, and you no longer have to worry about if your children will suffer from asthma because of smog.

Today, you may face a number of issues I could have never imagined. My hope has always been that the United States' efforts to combat climate change would create a cleaner future for my descendants and future Nevadans. I hope that you are no longer burdened with the issue of climate change and can enjoy more of the Nevada I have always known. But if you face similar challenges, draw strength from my experiences and continue to fight for a cleaner environment.

A U.S. Senator from Nevada, Harry Reid is a longtime member of the Democratic Party and served a lengthy term as Senate majority leader.

A U.S. Senator from Nevada, Harry Reid is a longtime member of the Democratic Party and served a lengthy term as Senate majority leader.

Rock, Ice, Air and WaterDear Future Inhabitants of the Earth,

I was speaking with an environmental scientist friend of mine not too long ago, and he said he felt extremely grim about the fate of the Earth in the 100-year frame but quite optimistic about it in the 500-hundred year frame. "There won't be many people left," he said, "but the ones who are here will have learned a lot." I have been taking comfort, since then, in his words.

If you are reading this letter, you are one of the learners, and I am grateful to you in advance. And I'm sorry. For my generation. For our ignorance, our shortsightedness, our capacity for denial, our unwillingness or inability to stand up to the oil & gas companies who have bought our wilderness, our airwaves, our governments. It must seem to you that we were dense beyond comprehension, but some of us knew, for decades, that our carbon-driven period would be looked back on as the most barbaric, the most irresponsible age in history.

Part of me wishes there was a way for me to know what the Earth is like in your time, and part of me is afraid to know how far down we took this magnificent sphere, this miracle of rock and ice and air and water.

Should I tell you about the polar bears, great white creatures that hunted seals among the icebergs; should I tell you about the orcas? To be in a kayak, with a pod of orcas coming toward you, to see the big male's fin rise in its impossible geometry, 6 feet high and black as night, to hear the blast of whale breath, to smell its fishy tang—I tell you, it was enough to make a person believe she had lead a satisfying life.

I know it is too much to wish for you: polar bears and orcas. But maybe you still have elk bugling at dawn on a September morning, and red tail hawks crying to their mates from the tops of ponderosa pines.

Whatever wonders you have, you will owe to those about to gather in Paris to talk about ways we might re-imagine ourselves as one strand in the fabric that is this biosphere, rather than its mindless devourer.

E.O. Wilson says as long as there are microbes, the Earth can recover—another small measure of comfort. Even now, evidence of the Earth's ability to heal herself is all around us—a daily astonishment. What a joy it would be to live in a time when the healing was allowed to outrun the destruction. More than anything else that is what I wish for you.

Author of short stories, novels and essays, Pam Houston wrote the acclaimed Cowboys Are My Weakness, winner of the 1993 Western States Book Award.

Author of short stories, novels and essays, Pam Houston wrote the acclaimed Cowboys Are My Weakness, winner of the 1993 Western States Book Award.

This Abundant Life

I just flushed my toilet with drinking water. I know: you don't believe me: "Nobody could ever have been that stupid, that wasteful." But we are. We use air conditioners all the time, even in mild climates where they aren't a bit necessary. We cool our homes so we need to wear sweaters indoors in summer, and heat them so we have to wear T-shirts in mid-winter. We let one person drive around all alone in a huge thing called an SUV. We make perfectly good things—plates, cups, knives—then we use them just once, and throw them away. They're still there, in your time. Dig them up. They'll still be usable.

I just flushed my toilet with drinking water. I know: you don't believe me: "Nobody could ever have been that stupid, that wasteful." But we are. We use air conditioners all the time, even in mild climates where they aren't a bit necessary. We cool our homes so we need to wear sweaters indoors in summer, and heat them so we have to wear T-shirts in mid-winter. We let one person drive around all alone in a huge thing called an SUV. We make perfectly good things—plates, cups, knives—then we use them just once, and throw them away. They're still there, in your time. Dig them up. They'll still be usable.

Maybe you have dug them up. Maybe you're making use of them now. Maybe you're frugal and ingenious in ways we in the wealthy world have not yet chosen to be. There's an old teaching from a rabbi called Nachman who lived in a town called Bratslav centuries ago: "If you believe it is possible to destroy, believe it is possible to repair." Some of us believe that. We're trying to spread the message.

Friends are working on genetic editing that will bring back the heath hen, a bird that went extinct almost 80 years ago. The last member of the species died in the woods just a few miles from my home. Did we succeed? Do you have heath hens, booming their mating calls across the sand plains that sustain them? If you do, it means that this idea of repair caught on in time, and that their habitat was restored, instead of being sold for yet more beachside mansions. It means that enough great minds turned away from the easy temptations of a career moving money from one rich person's account to another's, and instead became engineers and scientists dedicated to repairing and preserving this small blue marble, spinning in the velvet void.

We send out probes, looking for signs of life on other worlds. A possible spec of mold is exciting—press conference! News flash! Imagine if they found, say, a sparrow. President addresses the nation! And yet we fail to take note of the beauty of sparrows, their subtle hues and swift grace. We're profligate and reckless with all this abundant life, teeming and vivid, that sustains and inspires us.

We destroyed. You believed it was possible to repair.

Geraldine Brooks is an Australian-American journalist and author, Her 2005 novel, March, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. She became a U.S. citizen in 2002.

Geraldine Brooks is an Australian-American journalist and author, Her 2005 novel, March, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. She became a U.S. citizen in 2002.

My Endless SkyDear Future Robinsons,

Back around the turn of the century, flying to space was a rare human privilege, a dream come true, the stuff of movies (look it up), and an almost impossible ambition for children the world around.

But I was one of those fortunates. And what I saw from the cold, thick, protective windows of the Space Shuttle is something that, despite my 40 years of dreaming (I was never a young astronaut), I never remotely imagined.

Not that I was new to imagining things. As you may know, I was somehow born with a passion for the sky, for flight, and for the mysteries of the atmosphere. I built and flew death-defying gliders, learned to fly properly, earned university degrees in the science of flight and then spent the rest of my life exploring Earth's atmosphere from below it, within it and above it. My hunger was never satisfied, and my love of flight never waned at all, even though it tried to kill me many times.

As I learned to fly in gliders, then small aircraft, then military jets, I always had the secure feeling that the atmosphere was the infinite "long delirious burning blue" of Magee's poem, even though of all people, I well knew about space and its nearness. It seemed impossible to believe that with just a little more power and a little more bravery, I couldn't continue to climb higher and higher on "laughter-silvered wings." My life was a celebration of the infinite gift of sky, atmosphere, and flight.

But what I saw in the first minutes of entering space, following that violent, life-changing rocket-ride, shocked me.

If you look at Earth's atmosphere from orbit, you can see it "on edge"—gazing towards the horizon, with the black of space above and the gentle curve of the yes-it's-round planet below. And what you see is the most exquisite, luminous, delicate glow of a layered azure haze holding the Earth like an ethereal eggshell. "That's it?!" I thought. The entire sky—my endless sky—was only a paper-thin, blue wrapping of the planet, and looking as tentative as frost.

And this is the truth. Our Earth's atmosphere is fragile and shockingly tiny—maybe 4 percent of the planet's volume. Of all the life we know about, only one species has the responsibility to protect that precious blue planet-wrap. I hope we did, and I hope you do.

After 36 years as an astronaut—with a tenure that included four shuttle missions and three spacewalks—Stephen K. Robinson retired from NASA in 2012. He is now a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, Davis.

After 36 years as an astronaut—with a tenure that included four shuttle missions and three spacewalks—Stephen K. Robinson retired from NASA in 2012. He is now a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, Davis.

Let Me Tell You a StoryWell, My Great Ones,

The Europeans finally tried to do something after all this time. We told them over and over again; we showed them how to sustain and live within the capacity of their environment; but for hundreds of years they continued to rape and destroy our mother, Earth. What they didn't understand was that it was too late. You will never get to see or hear the thousands of species of frogs sing their songs, and you will never get to see countless varieties of bees, butterflies and birds take flight or hear their wings flutter by you as you marvel at their bright and beautiful hues. I assure you that these creatures existed in great diversity, helping the world to stay in balance.

Right now in California, we are in a drought and have been for several years. No one listened when the rain stopped coming. People continued to use water for green grass in their front yards because they wanted to prove they could afford to waste more than anyone else, never thinking to appreciate water and save it to quench their thirst. Some people saved water by painting their grass green. Who would have ever thought people would paint grass? If they would just plant indigenous drought-resistant plants with healing properties, we could save water and make our own medicine. But that would put the big corporations who make the drugs that we have become addicted to go out of business.

My Precious Ones, I am so sad to say that those in power strayed so far from what is important, caring for each other and for our planet; that it left you and the continued existence of our sovereign tribal nations in jeopardy. I wonder, did they ever learn that we are interdependent, not independent? Everything that is done to the Earth, impacts us, and our survival.

My Dear Ones, let me tell you a story ... there once was a time when the rivers were full of many types of fish and the water flowed clean, clear and bright because the rain came for many months throughout the year. There was plenty of food for everyone, and we lived with the understanding that we are all interconnected. What happens next is up to you to remember what was and make what is, different. The power has always been yours. We, your ancestors, are waiting.

Tamara Cheshire is an indigenous adjunct professor of anthropology and Native American studies in Sacramento, Calif.

Tamara Cheshire is an indigenous adjunct professor of anthropology and Native American studies in Sacramento, Calif.

To read more letters or to write a letter of your own, please visit LettersToTheFuture.org. This is a collaborative effort between this newspaper, the Association of Alternative Newsmedia and the Media Consortium. You can also like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/LettersToTheFuture.ParisClimateProject.

No comments:

Post a Comment